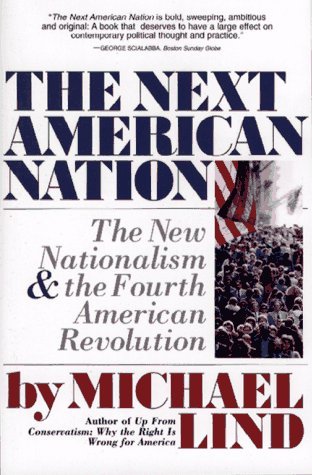

Michael Lind published his amazing work, The Next American Nation, in 1995. It’s a book about how different versions of the American republic have emerged periodically, following revolutions every hundred years or so. Seeing as it came out just before one of my favorite books about such cycles, The Fourth Turning by William Strauss and Neil Howe, it’s kind of strange that I never read it until now. It is the most egregious example of a book that came out in the Third Turning that I am finally getting around to reading in the Fourth Turning (there have been many others). I should have been comparing Lind’s revolutions to the Strauss & Howe cycle decades ago! But no matter, I finally read it, and in this review I will discuss what I found.

Lind describes three historical versions of the American republic: the one after the founding of the United States, a second one after the U.S. Civil War, and a third one following the Civil Rights era. He also speculates on a possible fourth republic in the future (which could be now, since he wrote this over twenty-five years ago). It’s interesting that two of Lind’s revolutions coincide with Fourth Turnings from Strauss & Howe, but the third one does not, and also that Lind does not identify the New Deal as the founding of a new version of the American republic. I have seen the same pattern in another theorist’s version of waves or cycles of political change, and I’ll get to that point later in this post.

To Lind, it’s important to consider that the United States of America is a nation, and that it has (or should have) a national identity. It does not make sense to think of the United States as a federation of separate national groups (as implied by the “nine nations of America” idea), nor should it be considered a collection of people united by an ideal such as democracy, or individual rights, or free market capitalism. The United States is a nation, like any other, and it’s not even exceptional. It is not, for example, the only settler society consisting of people who are mostly descendants of immigrants from the past few hundred years. It is not the only nation with a diversity of ethnic groups and religions. It is a distinct and unique nation, to be sure, but so are all others.

As a nation, each version of the American Republic has four identifying characteristics: a national community, a common ethic, an elite class, and a national political creed. Lind’s book is very orderly, and he explains what he means and describes these characteristics clearly for each version of the Republic. I will do my best to summarize what he wrote.

The First American Republic, the one founded in 1789, Lind calls the Anglo-American Republic. The national community of that Republic was people of Anglo-Saxon heritage, and the common ethic was Protestant Christianity. So you can see he is straight up accepting that, in its founding, the United States was an exclusive nation for a particular ethnic community – those we would later call WASPs, the original privileged Americans. The First Republic was dominated by an elite class of Southern planters, and its political creed was the decentralized republicanism of Thomas Jefferson.

Massive immigration of non-Anglo Saxons (Germans and Irish primarily) throughout the nineteenth century undermined this order. After the Civil War came the Second American Republic, which Lind calls the Euro-American Republic. He states that the Civil War could be understood as a war between the Anglo-American South and the Euro-American North. The Second Republic’s national community was white people of European descent, and its common ethic was “Judeo-Christianity,” in that it was for the most part inclusive of Protestants, Catholics and Jews. In fact, it is from this “triple establishment” of religions that we get jokes that start with “a pastor, a priest, and a rabbi…”

The Second Republic’s elite was the Northeastern business and professional class, what might be called the new bastion of WASPness, or those who could claim descendance from the Mayflower. It’s political creed was a more democratically inclusive form of federalism, still decentralized but with more universal suffrage, and undeniably white supremacist. It was during the Second Republic that the frontier closed, and we got the “melting pot” concept – that America was forming a distinct culture out of the cultural elements of its many different immigrants. It was during this time that the concept of “whiteness” expanded to include all Europeans, not just Northern Europeans. Still, the Northeastern WASP elites dominated, and it is from them that we get what might be considered the quintessential elements of American culture: baseball, football, and how we celebrate Thanksgiving and Christmas.

As already noted, Lind does not consider the Depression, New Deal, and Second World War era to be revolutionary or to have founded a new version of the American Republic. Instead, he identifies the next revolution as the Civil Rights movement of the mid-twentieth century, and declares that the Third American Republic, which he calls the Multicultural American Republic, was founded around 1972 with the end of the Civil Rights era and the establishment of affirmative action and racial preferences. The Multicutural American Republic doesn’t really have a national community, being something of an amalgam of different racial nations, and it lacks legitimacy in the public eye.

The Third Republic’s common ethic is one of ethnic authenticity – being true to whatever your particular race-based subculture is. Its political creed is multicultural democracy, reinforced by racial gerrymandering. Its elite is a white overclass, which maintains what might now be called the “neoliberal order” (though Lind doesn’t use that term), and allows a small number of non-whites into their class through affirmative action, which Lind calls a “racial spoils system.” This is a compromise made so that the white overclass can remain the elites without risking the unrest of another Civil Rights movement.

Clearly Lind recognizes the long shadow of white supremacy and white privilege in American history. But he could hardly be called “woke” (to use the current parlance); in fact he is generally considered to be a conservative. According to his Wikipedia page, in his works he upholds “American democratic nationalism,” which is basically the form of his ideal Fourth Republic. It’s a Republic that guarantees individual civil rights more universally, backed up by a vigorous yet limited central government – a vision closer to that of Alexander Hamilton than that of Thomas Jefferson, which perhaps explains the popularity of the musical.

In the Fourth American Republic (still to come), the national community is both a cultural melting pot and a racial melting pot, united by American English and an identifiable American culture. Its common ethic is what Lind calls “civic familism,” which is kind of a belief in the importance of family as the foundation of a stable society. Family life is private, and can be religious or not, and patriarchal or not; it can be whatever works for the particular family (think “modern family”), so long as it provides a stable base from which the family members can then engage publicly as responsible citizens. At least that was how I interpreted his argument.

The Fourth American Republic’s political creed is a national democracy where civil rights are uniform, and the law is absolutely color blind. This harkens back to the original civil rights vision of Martin Luther King, Jr., with his famous quote about judging people by their inner, not their outer qualities. This is what the revolutionary civil rights era was trying to bring about, before the compromise of affirmative action twisted its meaning and gave us the unsustainable racial preferences system of today. Or rather, the unsustainable system of the time when Lind wrote this book. Recently, affirmative action is under attack by the Supreme Court, which Lind might consider a step towards the Fourth Republic that he envisioned. But I haven’t seen anywhere that Lind agrees with this assessment.

Lind provides a long list of radical reforms that would be needed to bring about his revolutionary Fourth Republic, all meant to bust up the oligarchy and create a level playing field on which the racially-blind working class can thrive. These reforms include immigration restrictions, tariffs, progressive taxation, college tuition subsidies and caps, and an end not only to affirmative action in college admissions but also to legacy preferences. He warns that without these reforms, we could end up as a “Brazilianized” society with permanent racial castes, or succumb to a nativist backlash and a demagogue who attempts to restore the good-old white supremacy of the Second Republic.

Looking at the state of affairs today, in 2023, I imagine that Lind would recognize some things coming to pass that he wrote about in 1995. The rise of MAGA indeed seems like a nativist backlash with tinges of white supremacy (make America like the 1950s again). Its enemy in the civil conflict, wokeism, is like an entrenchment of the racial preferences regime of the “Third Republic.” So we are facing both of these possible negative outcomes that Lind warned about, and not much chance of achieving the reforms he advocated.

Michael Lind has written several more books since The Next American Nation, and frequently has opinion pieces published online. I haven’t read any of his other books, but from what I’ve seen of his online presence, he continues to beat the drum against oligarchy, and promote what he thinks are the best options for the working class. For example, in this piece he argues that we need to ditch neoliberalism and wokeism as tools of the elites, and need a coalition of pro-worker factions from both political parties to work together. He does not believe that we can achieve the Fourth Revolution by having one party or the other dominate in government; that will simply entrench the status quo, since those parties are captured by the elites.

As already discussed, it is notable that Lind considers the Civil Rights movement to be the Third Revolution that founds the Third Republic, rather than the New Deal, as identified in Strauss and Howe generational theory. I think this is because Lind is focused on understanding a nation as a cultural entity, supported by an instutitional framework, perhaps, but not defined by it. Strauss and Howe, in contrast, define their Crisis eras as periods of institutional transformation, or as they put it, changes to the external order. Roughly halfway between each Crisis, they identify another transformative era that they call an Awakening, in which what changes are social values – in other words, the internal order.

According to Strauss and Howe, the changes that Lind calls the Third Revolution were really changes to the internal order during the last Awakening. The “Multicultural Republic” that resulted is still the New Deal Republic, but with its institutions questioned and weakening, under assault from the new multicultural values. The reason this Third Republic (as Lind calls it) lacks legitimacy is that we haven’t yet fully passed through the Crisis era, from which a new institutional framework will emerge that incorporates (to a yet unknown extent) these new values. Once all the political dust settles from the Culture Wars battles now being fought in courts and legislatures, we’ll see how “woke” we end up becoming. When the political conflicts are finally settled, the new “Fourth Republic” will be accepted as legitimate, perhaps grudgingly by many, but legitimate nonetheless – at least in the sense that no one has the energy left to fight against it.

The other theorist who similarly identifies a new order emerging from a period later than the New Deal is Philip Bobbitt, with his theory of the market state as a new consitutional order coming out of the end of the Cold War. I tried to summarize his theory in a blog post some time back. I’ve actually posted quite a lot about the market state, and eventually come to the conclusion, in my own words: “that while Bobbitt is correct in his broader theory of periodic changes in the constitutional order, with the “market state” he has really just identified the priorities of the market-driven social era of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.” Bobbitt, like Lind, intuited a profound social change occurring in his time, and fit it into his theory in a way that made sense to him.

I think that Lind and Bobbitt both miss the New Deal era as a revolutionary period because of the focus of their respective theoretical frameworks. Lind is focused on national culture, while Bobbitt is focused on military strategy. To them, the New Deal may have seemed like a bureaucratic adjustment to the republic or constitutional order that came out of the Civil War, not an epochal event in itself. To Strauss and Howe, it was indeed epochal, part of the previous Fourth Turning, as defined by their generational framework.

It’s clear that Lind realized profound changes happened to American culture coming out of the 1960s and 1970s, a commonplace observation in social history. He labeled it the founding of a new Republic, whereas Strauss and Howe would have called it the beginning of the end of the Republic that came out of the New Deal era, with the real founding of a new Republic happening a couple of generations later, in the aftermath of the Fourth Turning that they predicted (and which we are now in). From a high enough view, I suppose, the difference is immaterial. The world is constantly in flux, and you can draw your lines wherever you want to try to make sense of it.

What’s important is that these different theorists identified a common pattern in the way social change plays out. Societies tend to go from an ordered state to a disordered one, as one would naturally expect, given entropy. At some point, after the order has broken down far enough, an impetus to restore order kicks in, and society is reordered, but in a new way. Because Lind identified the same pattern that Strauss and Howe did, his American Republics closely match the saecular orders of generational theory’s turnings, even though they don’t match exactly.

In The Next American Nation, Michael Lind lays out a hopeful vision of how the United States could remake itself along the lines of true racial equality and respect for individual civil rights, living up to an expansive interpretation of the ideals expressed at its founding. To get there requires a raft of sweeping structural changes to our social order, which seem impossible to achieve, after a quarter century of partisan politics and government gridlock, with cultural conflict and imploding civic trust making any semblance of order seem like a far away fantasy. What history tells us is that the conflict of this Fourth Turning cannot last forever; at some point its fuel will be expended, and like any fire it will burn out. Only then will we see order emerge from the ashes, but whether it resembles Lind’s Fourth Republic or not, we cannot know.