Still May the Dark Brandon Come

“Who is this gray patriarch?” asked the young men of their sires.

“Who is this venerable brother?” asked the old men among themselves.

-Nathaniel Hawthorne, “The Gray Champion,” 1835

Who, I ask, is this Dark Brandon?

I know you know of him. He arose from the meme wars on social media like some dark avenger, deflecting attacks from the MAGA armies. They tried to stop him, to undermine him with mockery. “Let’s go Brandon,” they cried, meaning it as an insult, but he just turned it around on them.

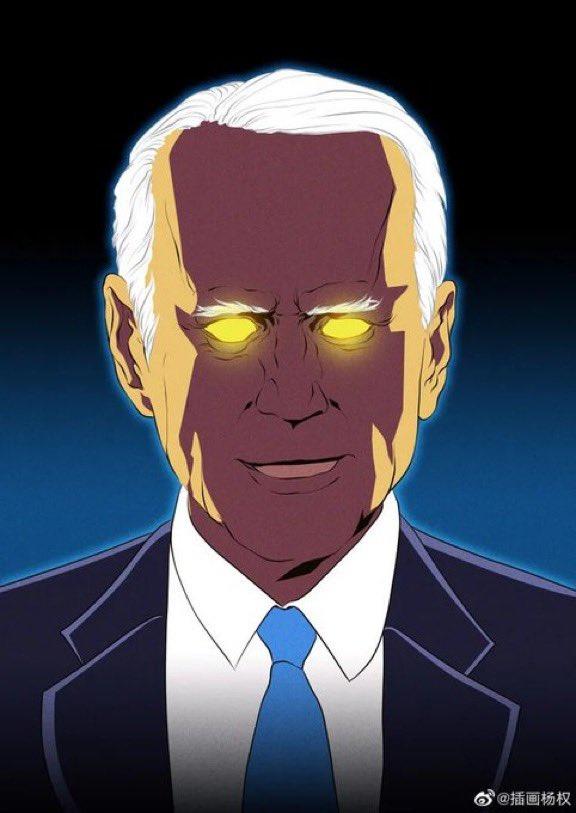

Wearing his cool sunglasses, he is unflappable. When he removes them, he reveals laser eyes, like some superpowered X man. Somehow, even though we live in such contentious times, he is able to get shit done.

Dark Brandon is this fascinating Internet construct, an alt-persona of the sitting President, Joe Biden. Biden has been in the U.S. government for decades, as a Senator for over thirty years, and then as President Obama’s VP for eight more, before being elected President in 2020. Over the course of his long career, he has never really stood out, just sort of always been there, part of the background, but also an important player in much negotiation and passing of legislation. This fits the archetype of his generation, the Silent Generation (Biden was born in 1942, and is the oldest President in U.S. history).

But how did he become Dark Brandon, a much more impressive and ominous figure than career Joe Biden?

In the U.S. domestic partisan conflict, fought primarily through memes in media and by gaming the political system, each side needs solidarity and consensus to prevail. I’ve blogged about this before, describing the polarization between a conservative red zone and a liberal blue zone. To maintain solidarity, each side needs to rally around their leaders, to support them no matter the circumstances. That is why it is so hard today to take a leader down by pointing out their moral failings; no one cares any more in the raw struggle for power.

The red zone has done very well mobilizing around their main leader, The Former Guy. This red zone leader is so fearsome that blue zoners like me can’t even say his name, as though he were a corrupt wizard from a fantasy universe. The blue zone needs someone to mobilize around like that, but in 2020 they chose the safe path of electing the Vice President from their last administration, who is kind of a holdover from the old neoliberal regime and a representative of the status quo. He was a strange choice for an inspiring leader.

Granted, as an old school neoliberal politician, Biden is effective. He is willing to negotiate with anyone in good faith, and while he does participate in the partisan conflict (warning against MAGA Republicans, for example) he doesn’t seem to take it personally. He doesn’t seek the limelight, and why would he? He’s been in the room where it happens throughout his whole long career. In a way, he’s fulfilling the archetypal role of his generation, tempering the passions of the younger generations and working out compromises between them, even if the end result is to delay an inevitable reckoning by continuing the endless mortgaging of the future (I refer to the debt ceiling crisis, of course).

But, as I already mentioned, the blue zone needs an awe inspiring leader, to sustain their morale in the ongoing sociopolitical conflict. And so they’ve crafted one out of the materials at hand. They’ve taken Joe Biden and memed him into a larger than life superhero they call Dark Brandon, a truly impressive guy you can really get behind.

In their theory of generational cycles, William Strauss and Neil Howe invoked the idea of the “Gray Champion,” based on a character from a nineteenth-century story by Nathaniel Hawthorne. This archetypal figure is a mysterious old man who appears when a society is in crisis, to rally the people and restore their sense of national pride and purpose.

According to generational theory, the Gray Champion is of the Prophet archetype. The examples from history that are usually used are Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Today the Prophet archetype is embodied in the elder Baby Boomer generation. Thus, Trump actually fits the bill, and if you think about it, in his own ham-handed way he is indeed trying to restore national purpose, or at least “greatness.” Here’s Neil Howe considering the matter back in 2017:

So what about Joe Biden? He was born just a bit too early to be a Baby Boomer, being instead a member of the Silent Generation. Wrong archetype. That explains his cool demeanor and his skill at negotiation. He’s so good at negotiating, in fact, that he outsmarted the House GOP in the budget process, or at least that’s what the blue zoners claim. But negotiating is not what the Gray Champion does. The Gray Champion rallies the people behind a cause, and you fight for that cause, come hell or high water. There is no negotiating involved.

So could Biden possibly be America’s Gray Champion, like Lincoln or FDR? There are some causes that Biden has championed, notable the defense of Ukraine, to which purpose he can be credited with rallying NATO, after the alliance was called into question by the previous administration. And he stands up for the values of the blue zone faction in the Culture Wars, arguably rallying his people to uphold the establishment of a diverse, inclusive version of the American nation (in contrast to what MAGA represents).

If in his demeanor or his personality Biden doesn’t quite fit the archetype of the Gray Champion, could he possibly grow into the role? There is a danger here of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Some theory predicts that a persona will arise, so we go looking for it. We see it where we want it to be.

But consider that the Dark Brandon meme arose on its own. Almost certainly, it did not originate with people who were familiar with generational theory and trying to revive a particular generational archetype. Rather, the meme came about naturally because of a deep-seated need by a political faction to have a leader who is strong and resolute. One they can have faith in and follow confidently into a dark and foreboding future.

In other words, today’s living generations are primed for the return of the archetypal Gray Champion. When you need one, you need one, even if you have to invent one in the form of Dark Brandon.

His hour is one of darkness, and adversity, and peril. But should domestic tyranny oppress us, or the invader’s step pollute our soil, still may the Dark Brandon come…

-Nathaniel Hawthorne, perhaps

Hawthorne quotes are from his short story “The Gray Champion,” which can be found here: https://www.ibiblio.org/eldritch/nh/gray.html