A Plea for Our Democracy

I have argued on this blog already that we are in a political era of partisan conflict between two factions, in which the stakes are power and control and the arguing is essentially over. It’s all about solidarity now, what Ibn Khaldun called “group feeling.” That’s why it’s a really bad idea for one of the factions to be turning against their own candidate at the eleventh hour. I don’t think a Presidential debate was really necessary, but it happened and there is no going back. Seriously, Biden got flustered facing an opposing candidate who is a pathological liar and expert baiter. That’s all, get over it.

The MAGA faction now controls one of the branches of the United States government, the Supreme Court. They are close to capturing a second branch, the U.S. Congress. And they have a Presidential candidate who commands massive loyalty; it make no difference that he is a convicted felon and a disgusting human being. The point is the MAGA faction has the solidarity to potenitally propel their candidate into a second term as President, this time shielded by the Supreme Court and more prepared to implement policy.

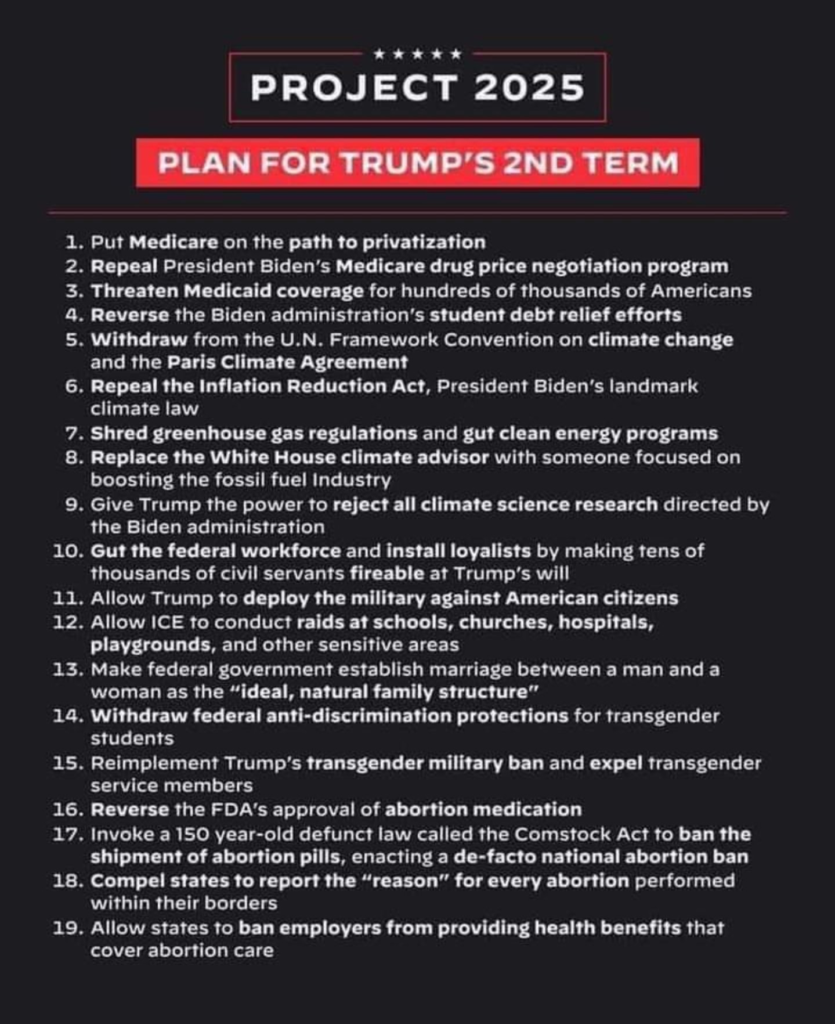

The MAGA faction has a plan should they take the Presidency, which you probably have heard of if not seen – Project 2025. It essentially rolls back the New Deal and aligns the federal government to Christian beliefs. The project’s leader has stated that “[W]e are in the process of the second American Revolution, which will remain bloodless if the left allows it to be.” Meaning they understand the stakes.

If what you want is a dictatorial President persecuting minorities and enforcing religious law, well I guess you know which faction you are in. If you are in the other faction (full disclosure, that’s the one I’m in) then I must reiterate that what is needed now is solidarity. That’s what it takes to win this power struggle.

Let me repeat what I wrote in an earlier post on this topic, written in May of 2022:

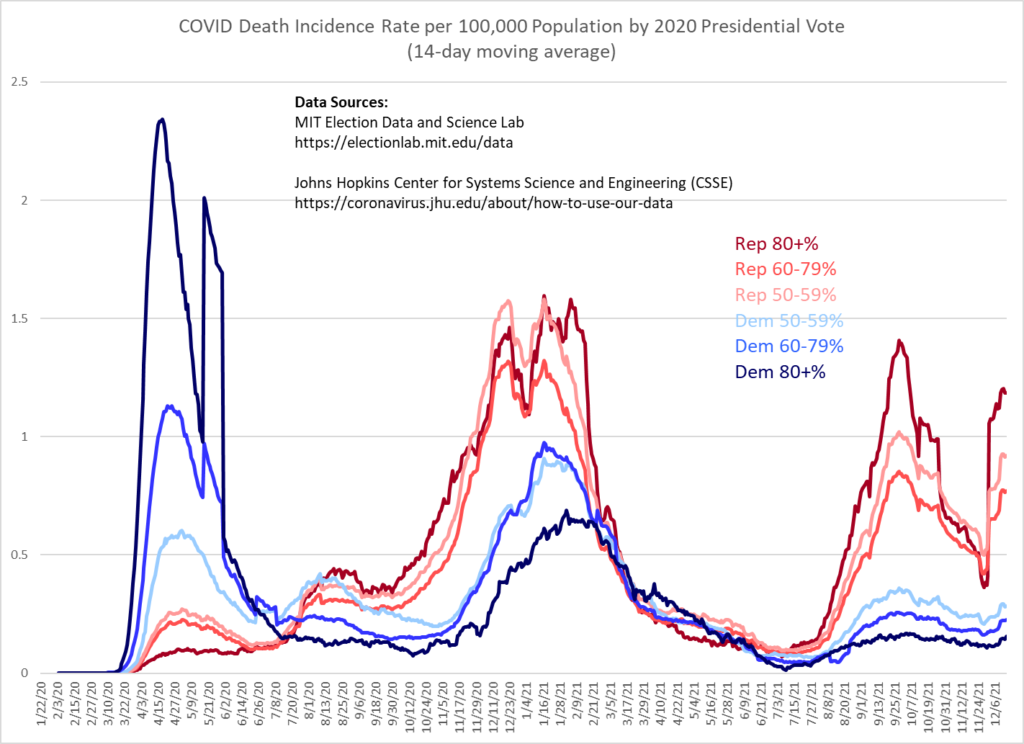

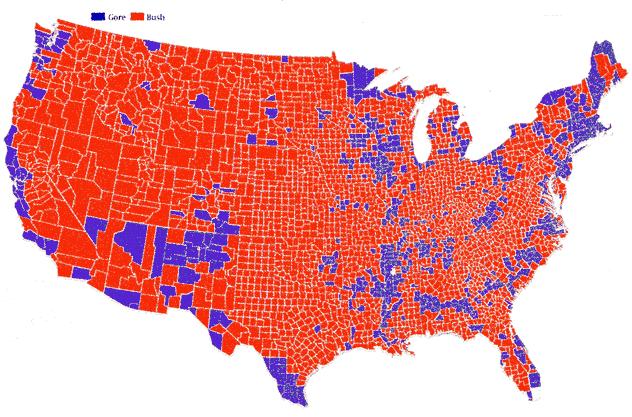

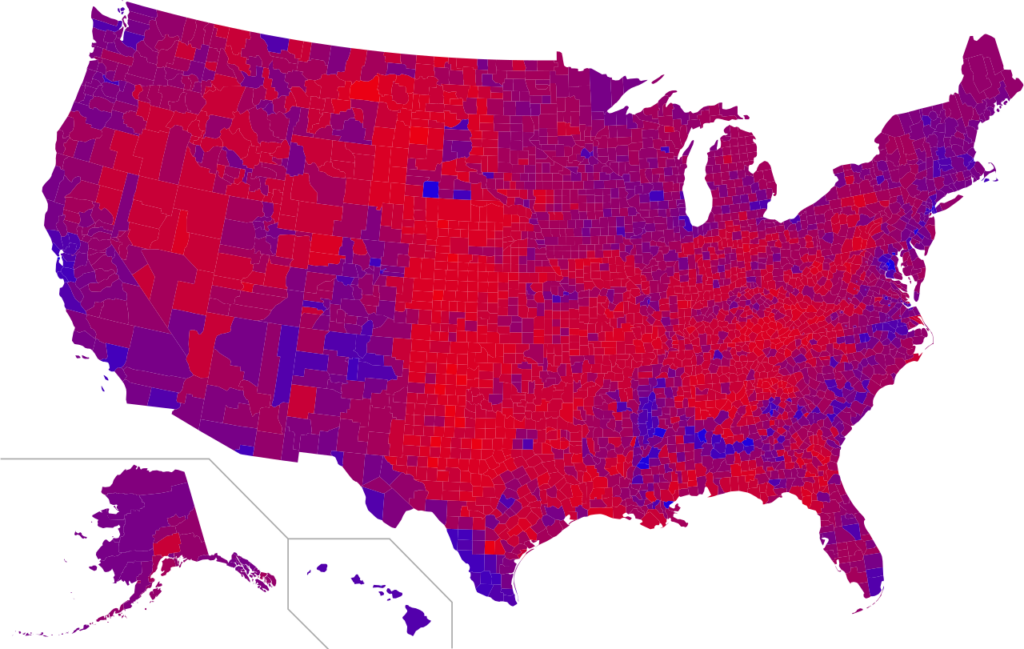

Which faction is currently favored in the conflict? A few years back I would have speculated that the red zone faction, rallying around former President Trump, had a stronger group feeling. They really seemed to have a greater solidarity of purpose than the blue zone faction, split between its progressives and moderates. But after the failed coup attempt in early 2021, my sense is that the strength of their faction just wasn’t quite enough to achieve superiority, and now they are on the defensive. However, I would note, as Khaldun might put it, that the red zone has been more clever at manipulating the laws of royal authority to favor their faction.

The Supreme Court decision granting the former President immunity from criminal prosecution was just such a manipulation of the laws, as was the way they maneuvered their judges into position in the court in the first place. This does not bode well for the blue faction. Luckily, awareness of this seems to have galvanized Democrats, and Project 2025 is now all over the media. But awareness and fear are not enough; they must translate into action at the ballot box. We must not allow ourselves to be cowed by negativity from profit-seeking media outlets.

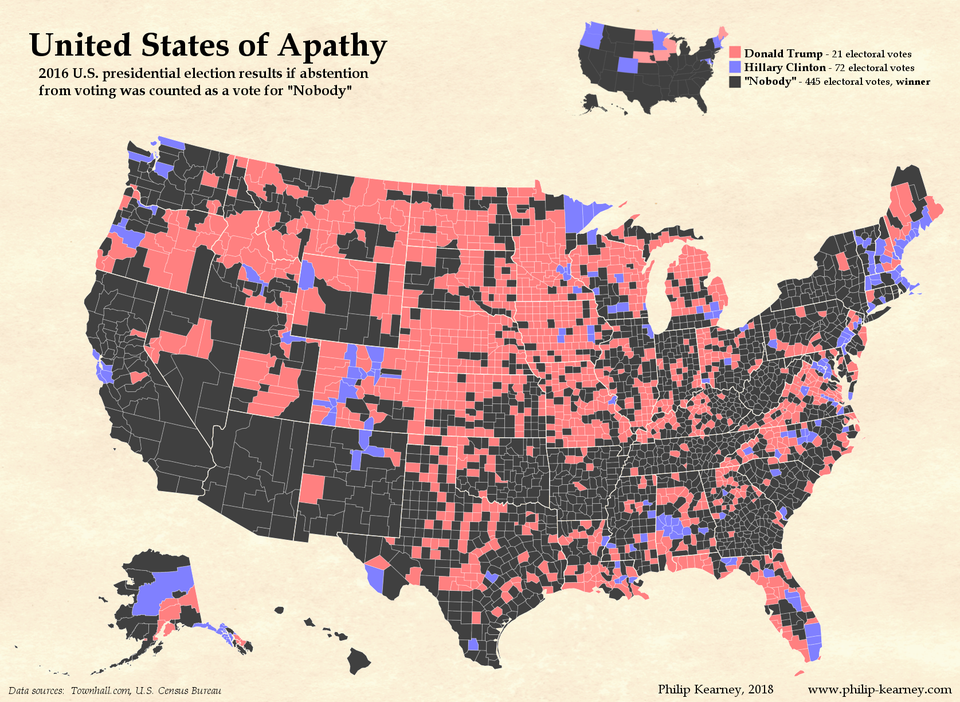

Probably if you are reading this post you are in the blue faction, as I am, based on my social network and who is likely to see this in their feed. Or maybe you think of yourself as not in a faction; but let me tell you, this is not the time for voter apathy or for a protest vote. Save that for a calmer era.

At this time, we need common purpose to resist a MAGA takeover. Should they win both the White House and Congress in this year’s elections, it is over for democracy in the United States. There will be no way to vote them out after that.

If you are reeling from the danger that we are in, that’s understandable. Remember that this is all part of a generational cycle. We are in a Crisis Era, a phase in the cycle in which the external world is reshaped. This includes political institutions, which is exactly what we are witnessing happenning. The MAGA faction has their plan to reshape the government, plain to see.

If you would rather have a government that upholds the rights of women and minorities, and respects the separation of church and state, then you must resist now, while you still can. You must vote for Democrats in the 2024 election. If you are not registered to vote, please register and vote Democrat. It is the only way to save our nation.