Science fiction often portrays a vision of a not-too-distant future, but a vision colored by the familiar elements and trends in thought of its own time. My favorite observation about the future as shown on the sci-fi screen is that hairstyles are going to be the same as whatever they were at the time the movie or TV show was made. When watching an older movie about the near future it’s always fun to see where they got it wrong when that future finally rolls around.

Blade Runner, released in 1982, is set in Los Angeles in 2019. Not the real 2019, of course, but an alternate one where the technology looks like it did in the 1970s and the atmosphere is like a 1940s noir film. It’s a wonderful movie, dark and moody, well written and well acted, and featuring a gorgeous Vangelis soundtrack.

I understand that the point of it is the story and the imaginative vision and that it’s silly to compare it to our time period. Nonetheless, I will. Here are some out of date elements in the scenery, compared to the real 2019:

- Big honking CRT monitors

- Neon signs

- Everyone is smoking in public

Of course, how could the people of 1982 predict that by 2019 smoking would be banished from public spaces (at least where I live; maybe it’s different in L.A.)? And that there would be LEDs, and flat screens, and the one thing that absolutely no pre-2007 sci-fi ever anticipates – smartphones?

To be fair, Blade Runner does get a couple of future technologies right:

- Voice recognition software

- Video calls

And then there are the predicted technologies that it might have been natural to assume would be coming in our future, but that our pathetic civilization has yet to achieve:

- Flying cars

- Off-world colonies

- And – oh yeah – Replicants!

It always strikes me how optimistic mid-twentieth century conceptions of the future of space travel are. Back then, it hadn’t been that long since the first orbital launches, and the U.S. space program was still prestigious. But what, no moon colony by 1999? No manned mission to Jupiter in 2001? Well, at least it’s not too late to get that warp drive invented, even if we do have to wait for some time traveler assistance.

As for the artificially created humans, well, they are the crux of the story of Blade Runner, and a sci-fi obsession going back to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. But their presence in the story is not a realistic extrapolation of technological progress. The closest thing we have to replicants today is artificial hamburgers. Our real world robots are dumb machines, and our real world ‘AI’ is the power of the Internet to collect and process vast amounts of data.

So I went to see Blade Runner 2049, and first I will report that it is just as good as the original. It has the same feeling of ominous wonder created through beautiful visual effects and an atmospheric soundtrack. It manages to take advantage of the 30+ years of advancement in film special effects (in the real world timeline, I mean) without detracting from suspenseful and meaningful storytelling. If you like science fiction movies in general and Blade Runner specifically then you will love this film.

So I went to see Blade Runner 2049, and first I will report that it is just as good as the original. It has the same feeling of ominous wonder created through beautiful visual effects and an atmospheric soundtrack. It manages to take advantage of the 30+ years of advancement in film special effects (in the real world timeline, I mean) without detracting from suspenseful and meaningful storytelling. If you like science fiction movies in general and Blade Runner specifically then you will love this film.

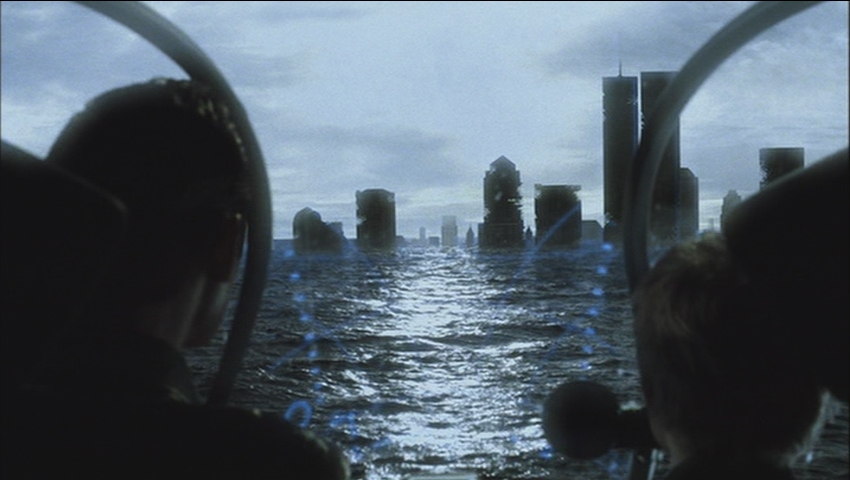

I don’t want to give too much away, but I will say that it is set in the same timeline as Blade Runner 2019, so there absolutely is no point in waiting until real 2049 to verify its predictions. In the movie’s version of 2049, there are still replicants, and off-world colonies, which is where you’d rather live, because Earth is still a mess, although the color palette of its dreary desolation has been updated a bit.

The 1970s look and feel of much of the technology is still there, which is neat, but here are some additions that reflect modern awareness:

- Drones

- Self-piloting flying cars

- Touchscreens!

- What if instead of growing a replicant, you programmed a virtual person into a computer, you could call it something else…

I will finish with some thoughts on the subject of artificial intelligence, which is huge in sci-fi film these days, in tandem with news feeds about the growth of the AI industry (which in the real world is building advanced information processing algorithms, not sentient beings).

In the original Frankenstein story, the monster confronts his maker, seeking acceptance, and the scientist creator laments that he has unleashed a destructive force. Both themes are prevalent in subsequent science fiction retellings, reflecting humanity’s yearning to understand its purpose in the universe, and fear that its technological progress has unmoored it from its origins. With Blade Runner (either one) you get all this, along with modern forebodings about overpopulation, ecological catastrophe, wealth inequality, and unbridled corporate power, artfully crafted to satisfy your need for continued myth-making.

We’ve been watching

We’ve been watching  I recently watched

I recently watched

So I went to see

So I went to see  I wanted to share my thoughts about a remarkable film: the latest Godzilla flick from

I wanted to share my thoughts about a remarkable film: the latest Godzilla flick from