One type of post I’ve made a lot on this blog is the “strategy review,” where I either review a theory of social and political change, or examine current events through the lens of such theories. Considering recent historical developments, I feel like it’s time for another one.

Over the years, I’ve gotten a lot of traction on this blog out of Philip Bobbitt‘s concept of the “market state” – a new constitutional order which he theorized was forming in the wake of America’s Cold War victory. In his framework, this was caused by changes in the security environment. With the ideological conflicts of the World Wars to Cold War era resolved, and free market capitalism ascendant, the state no longer derived legitimacy from controlling the economy and maximizing benefits to its citizens, in competition with other economic systems. Instead, it’s purpose was to keep its citizens safe and free markets functioning, to maximize economic opportunity.

This jibes with what other strategists, like Thomas P.M. Barnett and Peter Zeihan, have identified as the grand bargain the United States made with the world after WWII: we opened up our vast consumer market and invited other countries to embrace free trade, in return for which we stood as a bulwark against the Soviet bloc. Then we simply outlasted the Communists’ failure of an economic system. With Great Power conventional warfare a bygone in the nuclear age (the MAD doctrine), Pax Americana reigned over the Earth. Some even called it “the end of history.”

Things got messy after 9/11. It seemed history wasn’t interested in ending after all. The way Bobbitt understood it, in terms of his market state theory, is that in the new security environment, the threat wasn’t other nations making war on the West. Instead, it was transnational organizations taking advantage of the open networks of market state societies to infiltrate and cause harm – the 9/11 terror attacks being a spectacularly dramatic example. The point is, the market state had to adapt and develop countermeasures against these threats, with minimal reduction of economic opportunity for its subjects: that would be the test of its legitimacy.

The War on Terror and nation-building efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq could be thought of as the emerging market state’s efforts to assert just such legitimacy, led by the hegemonic “sole superpower” United States. We would just reformat failed states and turn them into free market democracies like us, with a few tricks (like Guantanamo Bay) to get around any legal concerns. It ultimately didn’t turn out so well, and we gave up after the Bush era, but arguably there were a lot of lessons learned about the shape of modern warfare that carry forward to this day (send in the drones!).

I’ve argued in other posts on this blog that what Bobbitt calls the “market state” is really just the zeitgeist of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries – an inner-driven, individualistic, commerce-minded social era. It was the age of neoliberalism, brought on by the Reagan revolution: a regime of free market principles aggressively pursued by government, on a global scale. The term “neoliberalism” is a bit fuzzy, and generally is used in the pejorative these days. Ever since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, there’s been kind of a consensus that neoliberalism was a bad idea, that it wrecked the middle class, and that we need to turn away from it, and from globalization in general.

In other words, what could be called the “neoliberal market state” was a creature of a relatively prosperous and stable era, when it was conceivable to have faith in markets and be comfortable with low regulation and an open, globalizing society. It wasn’t the end of history so much as a reprieve, during which the United States basked in its Cold War victory and enjoyed peak global hegemony. But the mood has shifted now. The public clamors for a more closed and orderly society, and a retreat from global affairs, which every President since Obama has provided.

This takes me to the recent Presidential election and the curious return of Donald Trump. Didn’t the people know that Biden-Harris was rolling back neoliberalism already, and was the best bet for the middle class? That Trump’s plans to cut taxes on the rich and impose tariffs on imports would hurt ordinary consumers? That his adminitration will deregulate capitalism to the benefit of the very wealthy, one of the hallmarks of the neoliberal regime we are supposedly rejecting? So why did they vote for him?

The election result could just be attributed to the incumbent-punishing effects of seething populism: everything sucks, and heads must roll! Alternately, the market state viewpoint might offer another explanation: informational warfare.

What I mean is, in the new constitutional order of the market state, the citizen is primarily a consumer. That includes being a consumer of media; that is, of information. In our somewhat free-for-all media envrironment, dominated by social networking sites, consumer-citizens tend to get pulled into either of two media bubbles, each one replete with the messaging of one of the two political factions vying for control of the government. It’s like two different versions of reality fighting for control over the minds of the masses. I’ve described this before as the “red-blue wars.”

It seems that in the recent skirmish that was the 2024 election, the red zone faction prevailed on the information warfare front. I have read post-mortem posts (there were so many this year!) that state just as much. The red zone faction simply has a more robust media ecosystem, which gives it a significant advantage. And, as I’ve noted before, they might also have more “group feeling,” or solidarity of purpose – another advantage.

But here’s another way to think about information war: it could be waged from outside! Meaning that, with the open and global nature of the Internet, “bad actors” who are not subjects of your government can infliltrate your media networks and influence your elections. This is a true test of the market state’s ability to sustain itself – is it even possible to govern at all in a wide-open society?

You might recall that this was the big story after the 2016 election: it was a successful Russian cyberwarfare operation, as Timothy Snyder bluntly put it. It was the first step to installing a Russian-style oligarchy in the U.S., and it seems like the 2024 election might be the last. In this interpretation, it wasn’t that the blue zone lost to the red zone. Instead, the United States lost to a foreign adversary, and was defeated in a market state war. The Russians outlasted us in the end, and we became like them!

I used to joke, during Trump’s first term, that we were transitioning from the “market state” to the “mafia state.” It doesn’t seem so funny now. The U.S. Constitution, stressed by decades of partisan gridlock, is fragile and might not survive a second Trump Presidency. He has no respect for the rule of law, and is enabled by cronies in the other branches of government. So it looks like we might end up with an entrenched criminal oligarchy. The only hope I have is that Trump is unfocused and distractable. But, as Tom Waits puts it, if you live in hope, you’re dancing to a terrible tune.

Arguably, “change voters” who put Trump in office this cycle were hoping for some kind of shake up that would at least put us on the path to fixing our broken system. That’s the only credit I can give them. But what will replace the market state that ostensibly has been trying to emerge these past decades? Trump’s cabinet of media personalities and tech bros are like a perverse enshrinement of the Reagan revolution – conservative pundits and Ayn Rand aficianados large and in charge. Isn’t that embracing the neoliberal market state?

Well, no, since the new regime promises to pull back from free trade, globalization, and military interventionism – all hallmarks of the neoliberal order. And the oligarchs at the top of the economic pyramid, like Bezos and Musk, are not interested in free markets. They want monopoly power, and the new administration will surely not stand in their way. It really is looking like we are reverting to isolationism and the rule of robber barons – because, you know, things were so great during the Gilded Age in the 19th century.

Were voters not aware that this was the future they were choosing? I mean, isn’t MAGA supposed to be a populist movement? Why did it put oligarchs in power? That’s where the idea of rightwing propagandists scoring an information warfare victory applies. Democracy is the tyranny of the uninformed.

Alternately, maybe MAGAs did intentionally vote for this bleak new order. Snyder has invented a term for this type of regime: sadopopulism. This is a kind of government that inflicts harm, but then deflects blame to stay in power. Certainly on brand for Trump. MAGA voters might be willing to suffer, so long as other people that they blame for their woes (immigrants, queers) suffer even more.

An even bleaker prospect: MAGA is an alliance between criminal oligarchy and a vicious backlash from social conservatives against the multiculturalism of the post-1960s era. It wants to replace the market state with a new version of the nation state that yokes powerful business interests to White Christian nationalism. If the nation state was legitimate because it looked out for the people’s welfare, then the Trumpian White Christian nation state is legitimate (in some people’s minds) because it looks out specifically for white Christians – maintaining their privilege over the rest of society.

At what point do we just go ahead and call it fascism?

If a MAGA takeover is resisted, it might only be because our judicial system allows that, in the “emerging market state” in the United States, consumer-citizens are empowered to define at the state level what their particular constitutional rights are. So states that are in the blue zone could reject White Christian nationalism, and institutionalize rights according to blue zone values – obvious examples being abortion access or sanctuary for immigrants.

This would amount to a fractionalizing of the U.S. along red zone-blue zone lines, which sounds quite plausible in today’s political environment. The problem with this, which Bobbitt himself has reflected on, is that it goes against the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal rights for all citizens under federal law. This may well be the direction in which our state is evolving. For many citizens of the United States, that would be a human rights disaster. There are already women dying in red states from lack of reproductive healthcare, and God help us if deportation camps become a reality.

Another problem with fractionalizing along red zone-blue zone lines is that it denies the United States a national identity. Can we then truly be a nation? Each side in our partisan conflict has a different vision of how our national identity should be defined. The red zone’s vision is exclusive and looks backwards in time, while the blue zone’s vision is inclusive and confront’s the realities of today’s world. Obviously, I favor the latter vision. But until the conflict is resolved, one way or another, the definition of our national identity – and with it our understanding of what makes government legitimate – will be unclear. Until then, we can only keep dancing to that terrible tune.

Well, there you have it. Another long post that probably overthinks the politics of our time by trying to force fit it into theoretical frameworks. I mean, is “information warfare” really a feature unique to the new “market state” of the 21st century? Wasn’t propaganda a big part of the political struggles and wars of the 20th century as well? Haven’t other societies faced political conflict with an ideological dimension, where persuasion and the spread of ideas was a factor – for example, the Religious Wars of the 16th century, or the Enlightenment Era Revolutions of the late 18th century?

Theories are useful for making sense of events and for structuring narratives, but might also impose limitations on our thinking. And while the past can inform us of what is possible, it cannot be a perfect guide to the future. Ultimately, the shape of things to come is determined by our unique choices, based on our needs and perspectives, in our specific location in history. Whatever version of “the state” is coming into being, and whatever name we give it, it will be one that makes sense to today’s living generations.

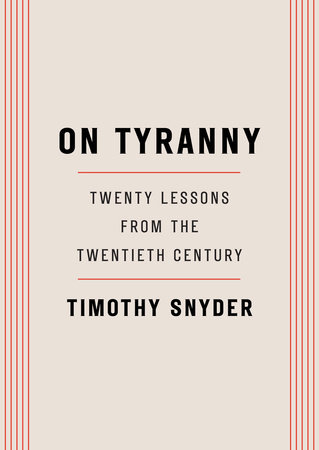

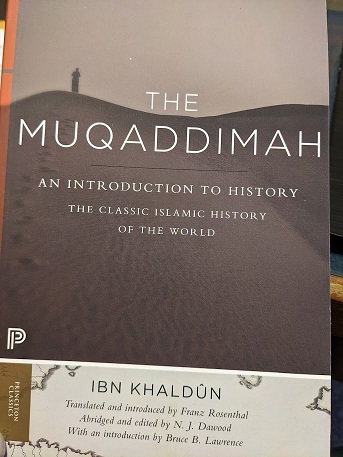

All I know for sure is that everyone is getting a copy of this book in their stocking this Christmas: