Strategy Review: Core versus Gap

Some time in the early 2000s I became acquainted with the thinking of Thomas P. M. Barnett, author of the book The Pentagon’s New Map. In this book he outlined a new paradigm for the deployment of U.S. military power in the post-Cold War era. Barnett was a strategist working for the Naval War College, and his geopolitical theory was radical, even – from the Pentagon’s perspective – apostate.

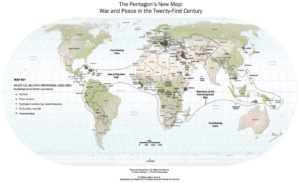

Basically, Barnett took a look at the post-Cold War military conflicts in which the United States had engaged, from the invasion of Panama in the waning years of the Soviet Union, up to the post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. His titular “New Map” divided the world into a “Functioning Core” of developed nations which were successfully integrated into the global economy, and a “Non-Integrated Gap” of failed nations where bad actors ran rampant and the U.S. was compelled to intervene militarily. From this simple concept a theory emerged of a new era of globalization in which the security threats to which the United States was responding arose from the disconnected status of the Gap nations – as he put it, “disconnectedness defines danger.”

The primary strategic goal for this new age was integrating the Gap with the Core, and as sole superpower America had a natural role to play in this process. Her conventional military force with its overwhelming power was what Barnett deemed a “Leviathan” force, and in conventional warfare the U.S. had no equal, as the recent invasion of Iraq had demonstrated. But what was also needed was a “Sys Admin” force for post-conflict stabilization (winning the peace); this is where allies with strong traditions of peacekeeping might come into play. With the right rule set for military intervention in the Gap, the end result would be increased connectivity with the Core. The military would just be kick starting this process; once the umbrella of security was provided, the private sector could take over. Globalization would spread, the Gap would shrink, and the world would be safer.

Barnett gives great presentations, and his “New Map” Brief is a classic. It was made in the early 2000s, at the heyday of his theory. The post-9/11 mind set was still fresh, and the U.S. security establishment was energized, as it struggled with the problems unleashed by the shock of 9/11 and subsequent U.S. response. In the brief Barnett preaches against the urge to throw up barriers to immigration and travel, to “firewall the Core against the Gap,” as he puts it, and encourages embracing globalization. As the 2000s continued, two sequels to the book followed which further developed his ideas.

Meanwhile, the Iraq War fiasco played out, and post-conflict stability proved elusive. I think Barnett’s theory lost its luster as a result, even though it never supported the careless invasion with no follow-up strategy practiced by the Bush administration (what he called “drive-by regime change”). Barnett never advocated that the U.S. become a “global cop” or act unilaterally (I remember him supporting Kerry in 2004), but rather that, with her preponderance of military power, the U.S. would inevitably end up shouldering much of the burden of conventional military action when it was necessary. But to shoulder that burden requires will, and after the long drawn-out suffering of the Iraq post-War, America lost that will, and through the Obama era and into the Trump era has withdrawn from the world.

At heart, Barnett’s theory is not militarily but economically deterministic, as he confirms in a blog post about a historian’s review of the third book in the trilogy. America as the victor of the Cold War had gifted the world with a free-market system which was elevating the bulk of humanity in the formerly impoverished Third World into a global middle class. In a world leadership role, presumably natural for a superpower hegemon, she could guide the development of that system and reap the most benefit from it. But after withdrawing into isolationism (“navel-gazing”), which is the choice the country has made, the system will continue to develop without her, its rules determined more and more by the new rising powers.

It’s nice to see that Barnett is still thinking strategically and creating briefs; there are links to a 2015 presentation up on his site. I recommend checking them out, because he is brilliant, a frank and humorous speaker, and he always makes you see things in a new light, or points out a trend or relationship that you weren’t aware existed before. Just the sort of thinking we need for the 21st century.

This is the third in a series of reviews of books about the Third Turning which I am finally reading in the Fourth Turning (the first two are

This is the third in a series of reviews of books about the Third Turning which I am finally reading in the Fourth Turning (the first two are  The latest audio book I have for driving in the car is the provocatively titled

The latest audio book I have for driving in the car is the provocatively titled