A Book about a Crisis Era

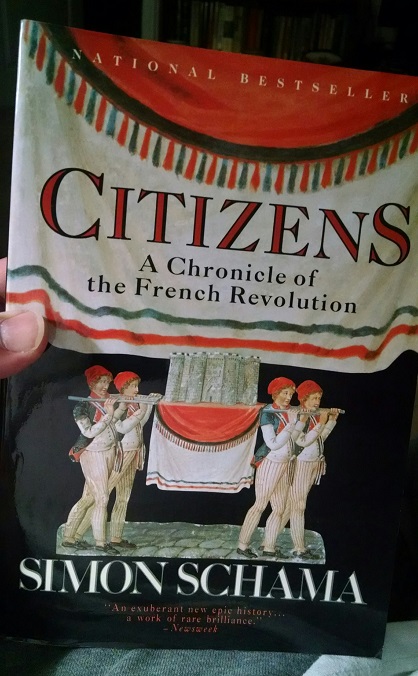

Some time ago I started reading Citizens, by Simon Schama. I finally finished it and posted a review on Goodreads, as part of my reading challenge. Here is the review reproduced for this blog, as well as some additional thoughts on what lessons the French Revolution might have for our own time.

First, the review.

At 875 pages (not counting the bibliography and index), Simon Schama’s Citizens looks like a formidable work to tackle. But his eloquent prose and touching, personal approach to history make for an easy read. There is certainly enough to write about the French Revolution to fill 875 pages, covering the span of time from the Revolution’s origins in the Enlightenment Era, up to the dramatic events of Thermidor and the fall of Robespierre. I enjoyed it all; this book is, as they say, a real page-turner.

In his narrative, Schama focuses on the individuals whose stories comprise the overarching epic of France’s transformation from floundering Monarchy to militant Republic. These are his titular citizens, and theirs is a shared journey through the gates of history, in which their identities shift from that of their prescribed roles in the old regime, to that of free and equal members of a common fraternity, devoted to the fatherland. And woe to those whose devotion was found insufficient, as conflict and violence swept through French society like wildfire.

The brutality of the violence and the fervor of the mobs which challenged the authority of every French government of the period, monarchical and Republican alike, is the most startling aspect of the Revolution. Schama disavows the idea that this was class warfare brought about by the disaffection of France’s poor and underprivileged. Not that there were no disaffections; these were famously written down in the lists of grievances presented to the King at the fateful convening of the Estates-General. But the impetus for change came from all levels of society. Many aristocrats and episcopalians were pushing for reform; for a Constitutional Monarchy in line with the ideals of the Age of Reason and the Rights of Man, inspired by philosphers like Thomas Paine and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. They did not anticipate that in a few short years their King would be dead and they would be fleeing the Terror of the radical Republicans.

Schama’s narrative shows a society consumed by a kind of madness for a new political identity and national rebirth. The French Revolution wasn’t a mechanical process of adjustment to modernity, driven by material circumstances. It was a conscious, creative effort of the human spirit. Material circumstances merely limited the scope of the change that Revolution could effect, particularly in economic conditions. And it was the limits of the human psyche itself that prevented the rapid succession of governments from ever establishing political order, without ultimately resorting to totalitarianism and mass murder, in an awful premonition of the horrors to come in a later century.

In this fascinating story of a nation’s struggle to redefine itself, we can detect lessons for our own time. In particular, the saga of the French Revolution warns of the dangers of partisanship, extremism, and the demand for ideological purity – all of which can sweep through a people like a tidal force, and drag them toward an unavoidable fate. It’s a warning we should well heed today.

Now for some additional thoughts on parallels between the French Revolution and our times.

There are two obvious rhymes between our time and that distant time in French history. One is the effects of extreme partisanship – how it creates an unbridgeable gap between the two sides, limiting people’s thinking to conform with their particular partisan view (we call it the “echo chamber” today), and how it completely disempowers political moderates (good luck, Joe Biden). The other effect, related to the first, is how easily misinformation spreads. The rumors that spread through French society, causing massive fear and anxiety, way back in the late 1700s, are no different than the “fake news” of today. As they say, the first casualty of war is truth.

As for the terrifying levels of violence, mentioned in the review, I will say that it is my great hope that we are past that. It was a more violent time back then. Life was cheap. But certainly there are violent, extremist elements in our society today, lurking in the background like the spectre of dangers past. And we are in dangerous times.

We are in a Crisis Era, like the one that France was in during the Revolution. Our society will – indeed, must – transform, just as France’s did, though it will not be the same kind of transformation. We have a mature Republic, not one that is or has just been formed, and though it is straining, it is still intact. Now we are in a great test to see if our institutions can adapt to the challenges of the 21st century – if we can muster our own spirit to face the great difficulties ahead.