Book Review: The Master Switch

My latest reading escapade has me perusing The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires, by Tim Wu. He is a law professor who is currently an official in the Biden White House, specializing in technology and antitrust. He is also, in fact, the coiner of the term “net neutrality,” which is just the legal concept of a “common carrier,” as has been applied to telephone communications, but extended to the Internet.

In The Master Switch, Wu analyzes technological and industrial development in the fields of telephony, radio, film, television, and computer networking. He identifies what he calls “the Cycle,” in which monopolist companies consolidate control over particular information technology markets (the empires), only to be challenged when new technologies emerge in periods of “creative destruction,” borrowing a term from Joseph Schumpeter. But whoever comes out on top in the new technological era simply replaces the previous monopolist. A good example is the telephone overtaking the telegraph, with the once powerful Western Union (powerful enough to decide Presidential elections) taken down – if not out – only to be replaced by a new dominant monopoly, in the form of AT&T.

The cycle as Wu describes it reminds me of the technological waves from Debora Spar‘s book Ruling the Waves, which I have already reviewed in a series of blog posts. They are very similar concepts, although to my knowledge neither author has ever recognized the work of the other. Despite the similar concepts which are their subjects, the two books are different in structure. Spar focuses on one technology at a time, whereas Wu jumps around between the technological fields, sticking to an overall chronological narrative. Either way, both authors end up in the Internet era, though Wu arrives ten years later. I noted in my review of Spar’s work that it would be great to get her opinion on how the Internet wave looks now, seeing as she was writing at the end of the dot com era (just around Y2K), but I don’t think she pursued the subject any further. Wu has followed up with additional books, though I haven’t read any of them.

In addition to the Cycle, Wu identifies what he calls “the Kronos Effect”, wherein an established monopolist uses its power, and usually its close relationship with government, to suppress new technologies, just as Kronos in Greek myth devoured his own children for fear of being replaced by them. A good example is how the NBC/CBS duopoly of radio broadcasting networks successfully prevented the development of television until the technology was firmly under their own control. This is why TV started with the “Big Three” networks already established in radio (ABC split off from NBC in 1943), not because there was any natural reason TV couldn’t have developed differently. There were independent television companies throughout the 1930s, but they were unable to grow their markets, because of the anticompetitive actions of the established radio companies.

I didn’t know much about the early days of television until I read this book, and it gave me a good overview. The story is just one of the many things I learned about the history of technology and of the people who were intimately involved with the invention and development of so much that we take for granted today. Wu’s book is well written, and with short chapters is a quick and easy read. The jumping around between the stories of different technologies can be a little confusing, but it’s made up for by the overarching narrative of “the Cycle” and the efforts of powerful interests to suppress it.

Interestingly, Spar didn’t include the dawn of television in her history of technological waves. When I read her book, I found it odd that she skipped from radio in the early 1900s straight to satellite television in the late 1900s. But I speculate now that it this was because she couldn’t fit the early history of television into her wave pattern. Like Wu, she identifies the invention and entrepreneurship phases of new technologies. But unlike Wu, she doesn’t cover the scenario where entrepreneurship is suppressed by a powerful entity maintaining its information empire, destroying competitors before they can even arise. The mid-1900s, a staid and conformist social era, was precisely such a period in the history of information technology.

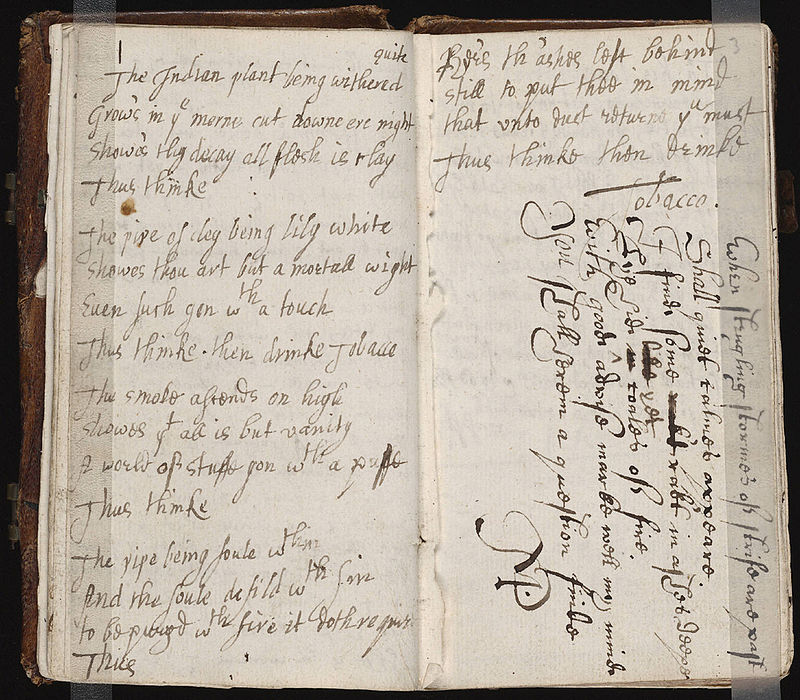

Concern for this pattern of anticompetitive economics imbues Wu’s book. It’s particularly concerning for information technology, because the corporations who dominate it control not just how we access information, but also what information we access. For instance, during the so-called “Golden Age of Hollywood,” private interests, via both the vertically integrated industry of the studio system and the privately conceived and enforced censorship of the Hays Code, controlled the nature of mass media content available to filmgoers for a solid two decades or more. Eventually both the industry and the social constraints were broken down, but conceivably much creative potential was stifled and lost forever in the interim. Conceivably, political orthodoxy was enforced; it is not a coincidence that the McCarthy era in politics occurred at the same time.

Similarly, the dominance of “Big Tech” in today’s Internet economy means a small number of corporations might end up becoming the gatekeepers of what news and opinion is available for consumption by Internet users, if they haven’t already. What is cancelling and deplatforming in today’s social media environment if not another version of a private sector censorship committee controlling what is considered acceptable free speech? Is a Twitter mob much better an arbiter of what is morally correct than was the National Legion of Decency? And if it is a better arbiter, because it represents a majoritarian viewpoint, then are we not living under mob rule, as Paris was during the French Revolution?

That raises the question of whether the impetus for controlling and shaping information is supply-side – driven by profit-seeking corporations and power-seeking governments – or demand-side – driven by a social need for consensus and conformity. I think it could be both. If there is a demand for order and regulation from below, it would only make it easier for those providing the supply from the top. And if the demand from below is for the loosening of regulation, it would be easier for the spirit of entrepreneurship to flourish. In other words, there might be a social cycle working in conjunction with an industrial cycle.

This is not something Wu addresses directly, being as he focuses on corporate actions and law, as befits his expertise. But he does hint at it in his narrative, recognizing how loosening social morality contributed to the decline in compliance with the Hays Code (compliance with which was always voluntary – as in not coerced by law). The idea of connecting the social cycle with the technological cycle or wave deeply interests me, and is what I have attempted to do in these series of posts looking first at Debora Spar’s book, and now at Tim Wu’s. Both authors recognized the same pattern, which must be deeply connected to human nature and human needs.

To conclude the book review, this is a very good read with a lot of fascinating tidbits about the development of information and communication technology, including biographical information about key players. You always get this human element in these narratives about the invention and commercialization of technology; personality is part of how technology empires are created. As already mentioned, patterns in economics and industry are connected to patterns in social mores and social needs, and in any social era there always seems to be someone poised to take advantage of social and technological change. A “man for his time and place,” so to speak.

In The Master Switch, Wu worries about the tendency for entities like corporations to arise and establish monopolistic control of new information technologies. Writing in 2011, he wonders if it will be different for the Internet, since by its nature it encourages openness and interoperability. From the vantage point of 2021, I think he would agree with me that the new monopolies have formed; we don’t have the term “Big Tech” for nothing. There may well be inexorable forces of history and human nature at work here, driving us collectively toward this state. This means a big challenge for Wu, in his official policy role, guiding the President on technology and competition, but it doesn’t mean that it isn’t worth the effort to mitigate against the downsides of information empires, or even try to stop them from forming altogether. I wish him the best.