A Millennial Learns the Hard Way to Act Her Wage

Recently we enjoyed the Netflix limited series Inventing Anna, based on the real-life story of a young woman who scammed New York high society for a good while during the 2010s. A lot of the show focuses on the high life – international travel, high-end hotels, designer clothes, expensive food and drink.

It reminded me of how movies from the 1930s were often about the well-to-do; everyone is in top hats and tails or fancy dresses with low cut backs, attending parties with ever flowing champagne. What Great Depression?

Ernst Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise is a delightful pre-Hayes code 1930s film about con artists travelling in high society.

Those movies were a form of escapism, and I got a similar vibe from this show, with its Millennials living like the Kardashians. But that’s not the norm for Millennials, right? Millennials are suffering in this economy, right? From watching Inventing Anna, you’d barely know – there are no gripes about student loans or the impossible cost of living, just young people living large. That’s why it struck me as a parallel to the films of the 1930s; it’s entertainment obsessing and focusing on the lives of the wealthy, while pushing the troubled nature of the economy out of sight.

It might not be fair to say that the titular character Anna was simply a con artist. Aileen and I had a discussion about this after we finished the show. In my opinion, she wasn’t a straight-up scammer in the Jimmy McGill sense. She was self-deluded and trying to accomplish something using sheer gumption and wishful thinking; she was trying to “fake it until you make it.” She was living way beyond her means while attempting to get a huge loan for a business venture, for which purpose she engaged in some technically fraudulent activities. She got caught because she exhausted her credit, and was charged with crimes, convicted and sentenced to prison (she has since been released).

But what if she had pulled off her scheme? What if she had somehow gotten the loan and started the business and made it profitable and joined high society for good, to the point that she had a cadre of fancy lawyers who could clean up her little bit of fraud behind her. Fait accompli. Then she just might have been another highly successful “art of the deal” type scammer. Like, you know, the guy who was President of the United States at the time.

Critiques of the show and of the magazine article on which it is based have tied the story to the class issues facing Millennials, as well as to the erosion of standards of truth and honesty that characterized the previous administration. Young adults today see the lives of the rich and famous plastered all over media, even while the chance at upward mobility is denied them, with economic opportunity available to fewer and fewer people as income inequality worsens. Why shouldn’t they do whatever it takes to make it?

Anna Sorokin had none of the qualifications for entering the world of fashionable socialites, but the lure of that lifestyle was irresistible to her. So she invented the qualifications; she created a “German heiress” persona and she attempted to insert herself into high society simply by acting like the people there do. What’s astonishing is that, for a few years at least, it worked. All she had to do to become a socialite was to act like one.

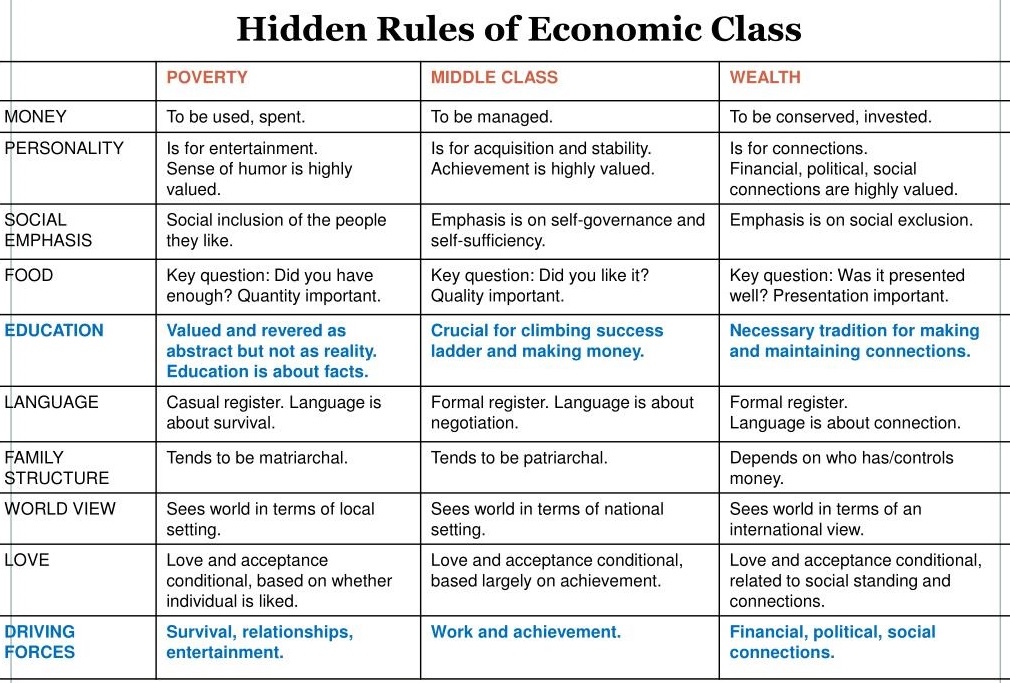

You might say that Sorokin didn’t act her wage, and for that paid a high price in reputation, and even lost her freedom (though I understand she got a handsome payout from the Netflix series production). What does it even mean to act your wage? This question leads me to the concept of “Hidden Rules of Class,” which I learned about in a workshop called “Bridges out of Poverty” that was held at one of my workplaces.

The concept of the hidden rules of economic class is that living in a particular socioeconomic class means having certain attitudes about and approaches to dealing with life’s basics. For example, with respect to money: when you live in poverty, money is simply something you need to survive. Easy come, easy go. But when you are middle class, money is something you have to manage – you have to tend it the way a farmer husbands livestock. When you are wealthy, money is now something to conserve. It’s more than a means to live, it’s a legacy.

If you’re wondering whether you are middle class or not, just ask yourself if you have to manage your money. If you have no savings or income surplus to work with and are just living hand to mouth, then, sorry, you are poor. But if you have the ability to live within your means, so long as you budget, and have enough leftover income after paying for necessities to plan how to use it – to save for big purchases or vacations (or retirement!) – then, congratulations, you are middle class. You might live in one of any number of tiers of the middle class, defined by the size of your house and the fanciness of your car and the cost of your vacations, but if you have to pay attention to your income and expenses, then you are middle class.

Only if you are truly in the wealthy class can you live like Anna Sorokin tried to live, casually travelling to anywhere on Earth and spending money on expensive luxuries without any thought. In that socioeconomic class, there is no concept of work-life balance, because you don’t work to live. You don’t go on vacation, you just live on the planet wherever you want, and naturally you choose pleasurable locations which for the middle class are occasional vacation destinations. You aren’t managing money at this point to get by, you are managing connections and exclusive memberships – your status is what you groom, not your account balances. The money takes care of itself.

That is how Anna lived, with incredible chutzpah, even though she wasn’t in the right class. And because she did it so naturally, she pulled it off – for awhile. It couldn’t last, of course, because there was no actual capital backing her up, just imaginary capital. I say she must have been self-deluded, because how else could she convince so many others of the reality of her delusional persona? Whether she realized it or not, she was taking advantage of the hidden rules of class to roleplay someone in the class she wished to be in, for as long as she could get away with it.