Rights vs. Responsibilities in the COVID Era

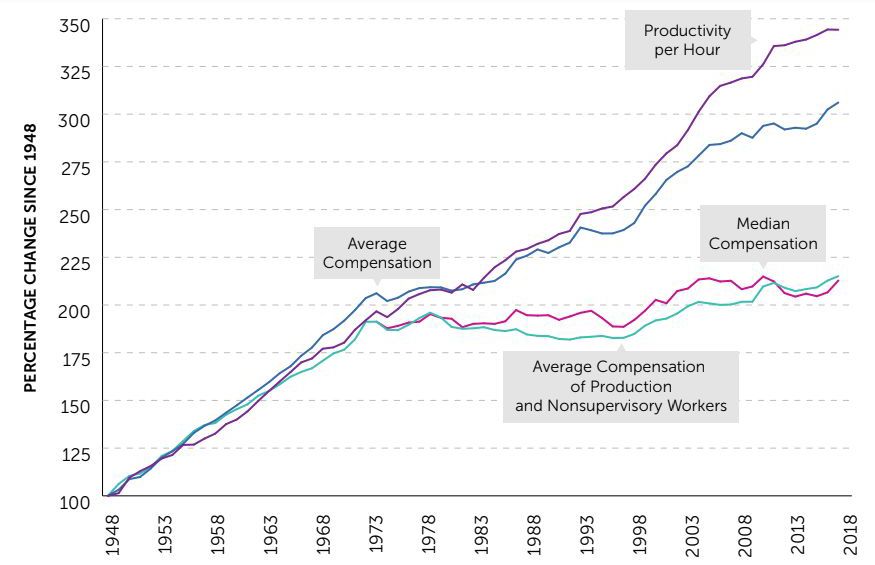

Take a look at the remarkable chart below, which shows death rates from COVID-19 for six different groups of United States counties. What distinguishes the groups of counties is the partisan voting rate, and what is remarkable is how much higher death rates are in Republican leaning counties than they are in Democratic leaning counties, after the first big wave, which hit primarily coastal megacities.

It’s not hard to draw the conclusion that this reflects the politicization of the pandemic, and how, in Republican-leaning parts of the country, there are lower vaccination rates and lower levels of compliance with mitigation rules such as wearing face masks and avoiding indoor gatherings. I’ve complained before about how insane this is, but here I want to give a little more thought as to why people might be motivated so differently in their behavior that they experience such disparate outcomes.

Here, I want to comment on how data like the above relates to two different ways of looking at the world. One is to see it from the standpoint of the individual, and their unique perspective. And the other is to see it from the standpoint of the collective of all people, which is what graphs like the above are doing. Graphs like the above are created by aggregating data – each week, a certain number of people die from COVID-19. Each individual death is a tragedy, and some deaths are unavoidable no matter how much we as a society try to mitigate against the spread of the virus. But looking at the aggregate data makes it plain how mitigation efforts do reduce overall suffering and death. That’s why we ask, as a society, for everyone to participate collectively in this effort.

The problem is, large numbers of people don’t want to see the world from this collective perspective. Their preference is to focus on the individual, and the rights of the individual. It’s like they see the dots on the graph, but not the curve. But one dot alone doesn’t give you any information, when you are trying to determine good policy. The curve, the collection of dots, is what lets you make an informed choice. The dots themselves just give you individual stories, what we call “anecdotal evidence,” which could be used to justify any policy. For example, as the graph above clearly indicates, some people in the counties with the lowest death rates do die from COVID-19. No place has a 0% rate. You’ll always be able to point to a case of a breakthrough infection in someone who was vaxxed and boosted and still got sick and died. But that one case alone is not enough to justify giving up on vaccination. To decide what overall policy is the most sensible based on one case and not the entirety of cases is foolish.

The same applies in other areas, like gun control. Simply put, firearms are a hazard and making them easier to access and carry around increases the risk to everyone of injury or death from firearms. It’s why we have this idea of sensible gun laws to regulate the use of firearms, making everyone safer, just as we regulate so much else in life. But a sizeable minority is obsessed with the individual right to bear arms, stymying lawmakers’ efforts to enact such legislation. This minority probably thinks that their arsenals will make a difference in upcoming political struggles. But however violently future political conflicts are resolved, what easy access to firearms will mostly do is increase the rates of suicide and homicide by firearm. I’m not even talking about mass shootings, I mean just ordinary incidents involving firearms.

Gun rights advocates will argue that it is unfair to deny them their individual rights just because of the negative consequences of other people’s choices. They are looking at the dots – you can’t take what’s mine based on someone else’s actions. For gun control advocates, the argument is that restricting gun rights will benefit the public in the aggregate. They are looking at the curve – overall suffering and death will go down if you change the rules. This is the same logic that goes into determining rules for the mitigating against the spread of the coronavirus. Restricting some rights, like the right to congregate indoors in large groups, will benefit public health, in the context of a highly transmissible and potentially fatal virus in circulation.

The zealous prioritizing of individual rights over collective good is what leads to memes like the one on the right, found on Twitter. It’s what leads to freedom derisively being called “freedumb,” when taken to the point of needlessly endangering lives. But those who won’t comply with mandates for the collective good aren’t really dumb, they are just prioritizing their rights as individuals over what is best for society as a whole. To them, compliance with authority smacks of submission to tyranny. They even have narratives based on historical occurrences to justify their resistance, even though the context is completely different now.

Maybe it would help for people to think in terms of both individual rights and individual responsibilities. Then you can keep your personal autonomy, but also recognize that your personal choices have consequences. Then you can see how you as a dot fits into the bigger picture of everyone else as a curve. Look again at the graph. It’s clear that for any one given individual, your chances of dying from COVID-19 are small. Not even half a percent of the country has. But if you are careless about transmitting the virus, you will help to kill some people. And that’s on you.