How to Act Your Class

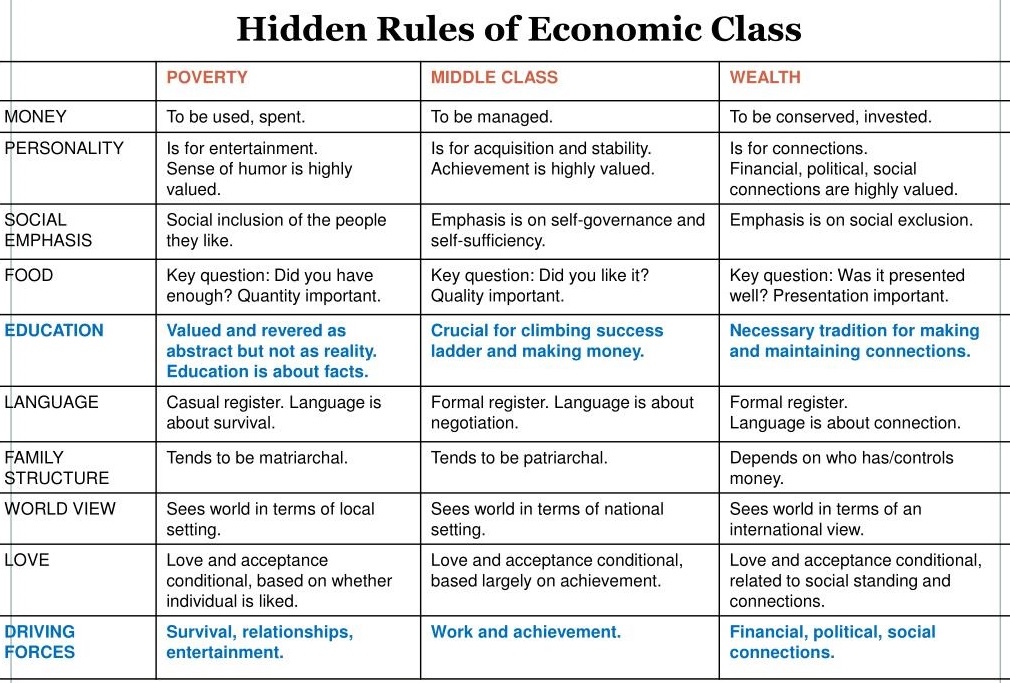

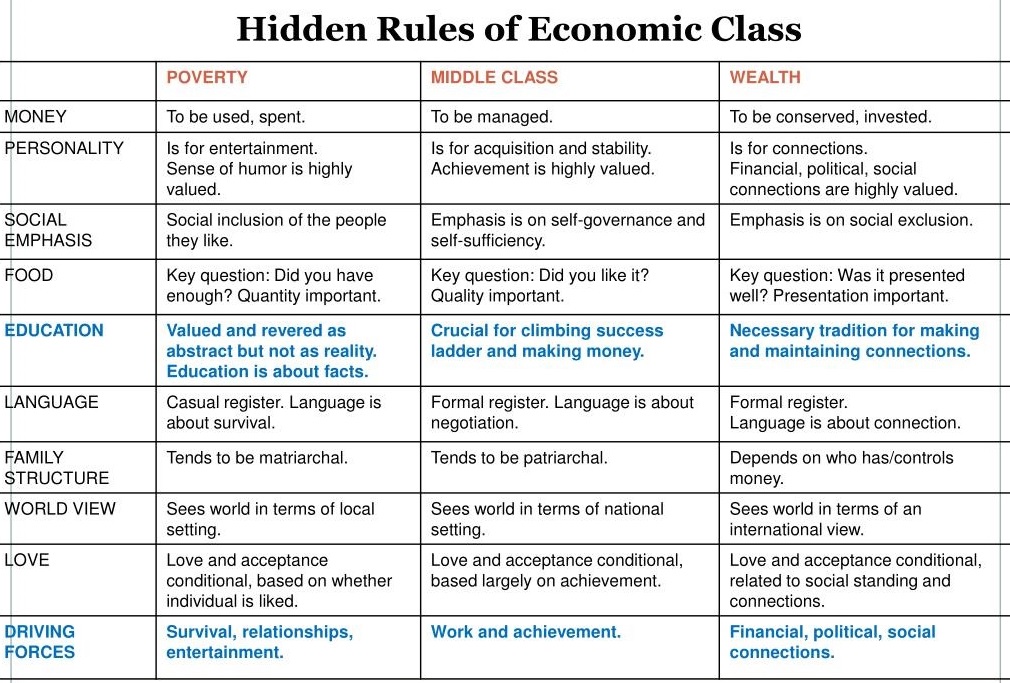

In my last post, on the Netflix series Inventing Anna, I noted how Anna’s posing as a German heiress had reminded me of a concept I learned about in a workshop on “Bridges out of Poverty.” This concept is “The Hidden Rules of Economic Class,” basically different attitudes and approaches to life based on whether you are poor, middle class, or wealthy. It was Anna’s attitude about money that made this connection for me; she was living a luxurious life as if money didn’t matter (wealthy approach), when it might have made more sense to be circumspect and manage her money like her friends did (middle class approach).

I’ve included the graph of hidden rules above (you can easily find this with an Internet search). You might notice that the wealthy approach to money is to conserve it, not to spend it, but my point is that the wealthy live in a higher tier of consumerism, and don’t relate consumer spending to money management. Instead, consumer spending is a way of signaling membership in the wealthy class. That is what Anna Sorokin was doing: living large to bolster the credibility of her invented heiress persona, and for awhile successfully pulling it off.

This kind of large living is only sustainable if you actually have a vast reservoir of capital on which to draw, which Sorokin did not have. That capital is what the wealthy want to conserve and invest, whereas the middle class, happy to have what little capital they do (at least they’re not poor, with zero capital), simply want to manage it so that they can enjoy as good a life as is feasible.

One way to think about it is with respect to end of life spending. If you’re middle class, you save up for retirement, so you can finally stop working (you probably won’t be able to work in your old age, anyway), but then all that savings gets consumed in the last decades of your life. You leave this world with nothing, just like you entered it. With retirement costs being what they are, you probably will burn through all your savings in your twilight years. It’s like the system is rigged to suck up all your energy, hapless little Matrix battery that you are.

But if you were wealthy, you would presumably want to leave the world with more than you started with. I mean, if you had a billion dollars at some point, you would want to die with more than a billion dollars to your name. You wouldn’t spend all that money on jet planes and yachts; you would want to leave a legacy, a foundation or something. That’s the wealthy “conserve and invest” rule for money.

There are other rules of economic class aside from how money is treated. For example, with respect to personality, for the poor it’s important to be fun and likeable (so people will want you around and take care of you), but for the middle class it’s more necessary to be emotionally stable and achievement oriented (so you can secure a wage income stream). This difference came up in conversation with Aileen back when she was doing the 2020 census. She noted that when she was in poor neighborhoods, people were nicer and more cooperative than the people in middle class neighborhoods, who were often outright hostile.

Now, there was some selection bias among the folks she was visiting, since census non-responders probably include people who don’t want to be bothered by the government in the first place. But when Aileen shared this observation, I immediately thought of the hidden rules of economic class. So I “Steveplained” (that’s the term for when I mansplain) to her that poor people are nicer because they don’t have much choice; they have nothing else to offer the world. Middle class people can afford to be jerks and to alienate others, because they can satisfy their needs with market transactions, seeing as they have money to work with. But if you have no money, you’d might as well be obsequious and hope for a handout.

I find this hidden rules concept fascinating, and have put some thought into how it might make sense to borrow rules from all the classes in order to be a well-rounded person. After all, there might be some scenario in which your class suddenly shifts, and it would be best to be prepared to fit in anywhere in the graph. Well, the most likely shift is from middle class to poverty, due to personal misfortune or possible society-wide economic collapse. But why not be resilient and even something of a class-doppelganger, like Anna tried to be?

So this is what I came up with.

From Poverty:

- Have a sense of humor and cultivate a likable personality. Be a person that others would want to have around, because you never know when you might suddenly be utterly dependent on others.

- Be mindful of the present circumstances and the local environment; don’t become isolated from your immediate surroundings. Get to know your neighbors!

- Be prepared to adapt to sudden change.

From Middle Class:

- Cultivate professional skills and the ability to continue earning income. Society hasn’t collapsed yet, and you want to earn while you can.

- Manage your money well, and also your physical and mental health, with consideration for the future.

- Be aware that choices matter and that you can change yourself for the better.

From Wealth:

- Think about what you can preserve for posterity, especially considering that you will never actually become wealthy. But you can still think of leaving a legacy of specialized knowledge, valuable collections or keepsakes, and your philosophy of life.

- Network. It’s always good to have connections.

- Maintain traditions and a sense of decorum.

That’s what I distilled out of the hidden rules of economic class. I can’t honestly claim that I follow all the rules in the lists above fully. Rather, I gravitate toward the middle class way, being something of a shut-in, and relying on my skilled wage income to buffer my family from life’s hardships. I like to think I’m a nice guy, but sometimes I get very cranky with my fellow human beings! I’m sure you understand.

I hope you have found these ideas illuminating, and are as intrigued as I am by this framework for understanding economic class. Maybe you will recognize some of these rules at work in your own life, in ways you hadn’t thought of before.