The Generational Shift in the Supreme Court

The confirmation of Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson as the 116th Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court is being hailed as an historic event. From reactions on social media it is plain that partisan blue zoners are relieved that the latest replacement on the Court has occurred during a Democratic Presidency, and succeeded despite the partisan split in the Senate. No one could forget the Republican controlled Senate’s political tactics in 2016 that handed the nomination of Justice Antonin Scalia’s replacement to a Republican President. That Jackson is the first black woman to serve on the Court is also rightfully being hailed as an important historic milestone. It reflects the long secular trend of the elevation of women and minorities as equals in our civil society. It is meaningful, in my opinion, that this historic moment occurred during the Presidency of Joseph Biden, who is from the generation of the civil rights movement – the Silent Generation. This moment is a fitting capstone to his generation’s legacy of fairness and inclusion in American life.

There has even been some notice of the fact that with Jackson’s appointment, the Supreme Court will, for the first time, have four women Justices serving on it. This reflects another secular trend of increasing gender equality on the Court. The first woman Justice was appointed in 1981 (O’Connor); this increased to two women Justices in 1993 (Ginsburg) and then to three in 2010 (Kagan following Sotomayor’s replacement of O’Connor). Ginsburg was also replaced by a woman (Barrett), suggesting that not even President Trump could bring himself to interrupt this historic progression.

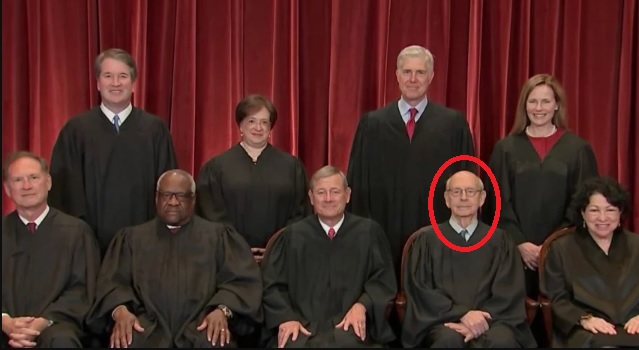

There’s another story that seems to have been lost in the shuffle. Take a look at the birth years of the current members of the Court. The Justice who is retiring and being replaced by Jackson is Stephen Breyer, born in 1938. He is the last remaining member of the Silent Generation to serve on the Court (the first was actually O’Connor; only six members of his generation have served on the Court). After Breyer’s retirement, all of the Justices will be either Boomers or Gen Xers. Jackson won’t just be the fourth woman on the Court, she will also be the fourth Gen Xer. This is another historic moment for the Supreme Court: the replacement of the Silent Generation by Generation X.

The other three Gen Xers on the Supreme Court were all appointed by President Trump. It is not surprising that Trump was able to find suitable red zone aligned jurists among this generation, which leans conservative and Republican. These three appointees may well be his administration’s most lasting legacy. They will steer the Court in a conservative direction for a long time to come. Even if, by some twist of fate, Biden should get the opportunity to replace another Justice, the Court will still be majority conservative (5-4 instead of 6-3). What does this new alignment, both generational and ideological, mean for the future of the Supreme Court?

I am not a legal scholar, so I can only speculate from the perspective of an educated layman. One thing I think is certain is that we will see breaks from precedent. This is already evident in the uncertain fate of Roe v. Wade – the dreaded (by blue zoners) overturning of that decision may be coming. One of the Gen X Justices, Gorsuch, reputedly disdains precedence and would prefer to craft his own conservative judicial philosophy. This sort of independence of thought is just what you would expect from Generation X.

Another trend I see is the continued success of the conservative mission to roll back the administrative state (a Silent Generation legacy) in favor of individual freedoms (a Generation X legacy). Case in point: the recent Court ruling that struck down the Biden administration’s vaccination mandate. Given her background as a public defender (the first to be appointed to the Supreme Court), Jackson herself might be inclined to rule in that direction.

Once Breyer has retired this summer, only one Justice will remain on the Supreme Court who was appointed in the twentieth century: Clarence Thomas, who will be the oldest, in his mid-70s. No serving Justice will remain from a generation older than the Boomers, and there will be four from my generation, Generation X, all appointed in the past five years. It’s actually quite remarkable that all of the Supreme Court Justices will be younger than both the President and the Speaker of the House, and that their average age will be slightly lower than the average age of U.S. Senators.

You would think that the Judicial branch would be where the old wisdom of the country resided, but a move to pack the Supreme Court with conservative thinkers has put my generation there instead. This historic generational shift in the makeup of the Court will have repercussions for years to come. Long-standing legal precedents and regimes that have been taken for granted are clearly in for a significant upheaval.