I’m going to return to looking at the list of patterns to expect for the living generations in the current social era, the Crisis Era in Strauss & Howe terms, picking up where I left off a few months back.

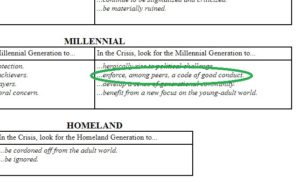

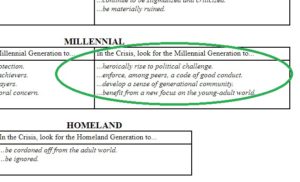

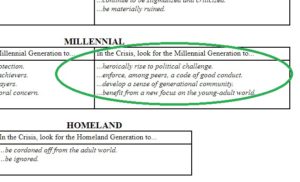

Let’s look at the remaining items on the list of predictions about the Millennial generation – that Millennials will heroically rise to political challenge, that they will develop a sense of generational community, and that they will benefit from a new focus on the young-adult world. For evidence, I will simply consider the kinds of news stories that have been prevalent on social media and the web in the past decade. So let’s start with the last item on the list.

Let’s look at the remaining items on the list of predictions about the Millennial generation – that Millennials will heroically rise to political challenge, that they will develop a sense of generational community, and that they will benefit from a new focus on the young-adult world. For evidence, I will simply consider the kinds of news stories that have been prevalent on social media and the web in the past decade. So let’s start with the last item on the list.

In the Millennial generation’s childhood era, which began way back in the 1980s, children benefited from a new focus on child-rearing. A wave of social change in the direction of increased child protection came in the form of mandatory safety rules, zero tolerance policies, and laws named after child victims (for example, Megan’s Law). I wrote about this on my old blog nearly twenty years ago.

Now that we are in the Millennial young adulthood era, the impetus for social change has shifted to the adult sphere of life. Political change may be stymied by partisanship, but a wave of social movements has risen in response to long-standing problems. These problems were tolerated when they affected previous generations – but no more.

A prominent example which can be thought of as zero tolerance policies reaching the workplace is the Me Too movement and its effects. This took off last year as a viral social media hashtag when a prominent Hollywood producer was accused by multiple women of sexual harassment. Since then, a flood of accusations has led to the downfall of many men in high places. Sexual harassment in the workplace has long been covered up by HR departments and endured by female employees, but in the Millennial era this may not be possible, or desirable, any more.

A less politically charged example is the new concern over reducing concussions to football players in the National Football League. The research into the problem began in the Gen-X era, but it was only ten years ago that the U.S. Congress compelled the NFL to act. An enormous settlement was agreed upon, which has benefited retired Gen-X players, but only after they sustained the injuries in the first place. For Millennials, a protocol is coming into place to reduce the prevalence of injuries in the first place.

Not that there isn’t a politically charged example connected to the NFL, by which I mean the Black Lives Matter movement. Football players kneeling during the national anthem are in solidarity with this movement, protesting police shootings of unarmed young black men. Though rates of violence have been declining for a generation, police killings still disproportionately affect minorities. In the past this may have been a topic for moralistic commentary in academia and the arts, but today it is the focus of a stubbornly persistent and controversial activist movement.

Another famous movement that seems to have come and gone is Occupy Wall Street, which protested income inequality and the corruption in government and finance that was brought into stark relief by the financial crisis and bailouts in 2008. The protests on the street may have ended, but they continue in the online world. On today’s Internet feeds there are endless posts about the difficulties faced today by Millennials trying to get by in the current economy – the burden of student debt, the impossibility of surviving on minimum wage, the need to delay life events like home buying or marriage until financial stability is achieved.

All of these difficulties were faced by previous generations, but now that Millennials face them there is a greater sense of urgency. Will these problems be addressed by drastic measure while Millennials are still young adults? Will student debt be discharged, and higher education be payed for by taxpayers, like primary and secondary education? Will the minimum wage be raised significantly?

This ties into the first item on the list of what to expect from Millennials – that they will heroically rise to political challenge. There is less evidence of this. Youth voting rates have increased slightly since their nadir in the Gen-X era, but have not come anywhere close to that of the great era of civic participation of the mid-twentieth century. Older generations still have a lock on government, which partisanship has rendered contentious and barely functioning. But time favors the young generation, and they will eventually make their voices heard.

All that is discussed above connects to the remaining item on the list – that Millennials will develop a sense of generational community. Just that fact the their generation’s name – originally coined by Strauss & Howe as part of an academic theory – has become a household word, and that news about them has become so prominent, shows how they are in the forefront of social awareness. Everyone is familiar, for example, with stories about how they are reshaping the economy. With the spotlight shining on them, it is hard to imagine this generation doesn’t have a strong self-awareness. If they can combine that awareness with an enforceable political consensus, they could reshape our society, and truly bring about a Millennial era.

Let’s look at the remaining items on the list of predictions about the Millennial generation – that Millennials will heroically rise to political challenge, that they will develop a sense of generational community, and that they will benefit from a new focus on the young-adult world. For evidence, I will simply consider the kinds of news stories that have been prevalent on social media and the web in the past decade. So let’s start with the last item on the list.

Let’s look at the remaining items on the list of predictions about the Millennial generation – that Millennials will heroically rise to political challenge, that they will develop a sense of generational community, and that they will benefit from a new focus on the young-adult world. For evidence, I will simply consider the kinds of news stories that have been prevalent on social media and the web in the past decade. So let’s start with the last item on the list. When we arrived in the city the station was so crowded that it took an hour to get to the street. A huge mass of sign-carrying people slowly made its way through the turnstiles to exit the metro, and finally we were in the open air. We found our way to the mall and suddenly were swept up into a throng of protesters, streaming from where the speeches had been made (speeches we had missed, since it took so long for us to reach the city) towards the White House. The chanting, roaring energy was indomitable. It was the backlash against the backlash.

When we arrived in the city the station was so crowded that it took an hour to get to the street. A huge mass of sign-carrying people slowly made its way through the turnstiles to exit the metro, and finally we were in the open air. We found our way to the mall and suddenly were swept up into a throng of protesters, streaming from where the speeches had been made (speeches we had missed, since it took so long for us to reach the city) towards the White House. The chanting, roaring energy was indomitable. It was the backlash against the backlash.