Off to Beach but First a Movie Review

Here we are at the height of summer, when the days are long and the UV radiation intense. We’re about to vacation at the Delaware shore, where we will be seeing the whole extended family, while celebrating my Dad’s 80th birthday. I’m looking forward to the trip, and to being (mostly) offline for the duration. But first, let me just share some brief thoughts on the Barbie movie, which we saw on preview night.

Note: many Barbie spoilers to come, so if you haven’t seen the movie, you might want to turn back. Go see it – it’s well worth your time – and have a wonderful summer.

.

.

.

.

You’re still here! You’ve already seen the film, or you don’t care about spoilers.

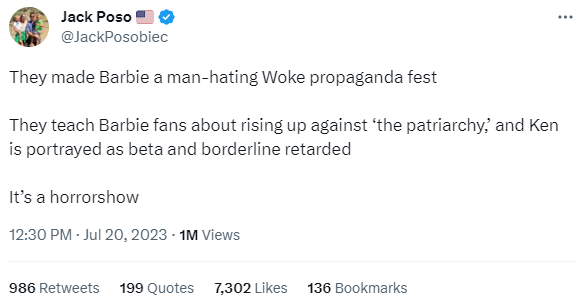

You’ve probably heard mixed reviews of Barbie. Some say it’s brilliant, others call it a hot pink mess (why can’t it be both?). And you may have heard there is some outrage coming from the political right, who accuse it of being “woke” and “gay,” presumably representing all that is wrong with society today. This outrage sentiment seems to be coming mostly from Millennial men in the alt-right.

It is true that the movie makes fun of men (in the form of multiple Ken dolls), though I wouldn’t say that it’s hateful in any way. You have to consider that the setting of Barbieland is a fantasy world, an imaginary realm of dolls that girls are playing with. It’s Barbie and Ken in this fantasy land, not the other way around. And this place is absurd; all the Barbies are impossibly happy, living in dream houses that are facades, working at jobs that are completely unnecessary because where they live they don’t even follow the laws of physics. And yeah, Ken is secondary (or “beta,” as an alt-righter would put it), but that’s because this is a land of imaginary female empowerment.

Which turns out to be the point of the movie: when Barbie and Ken visit the real world, they discover that women are not, in fact, in charge. Life is messy and complicated, not a perfect dream where happiness is guaranteed, an entitlement that comes from simply existing. Whether you are a man or a woman, whatever your place in society, you will ultimately have to be grounded in yourself, and make the best of an imperfect world.

Barbie might be an inspiration, but no real woman could ever become her. Instead, women must contend with unrealistic expectations in a world of contradictions, as described in Gloria’s monologue, which is the crux of the film. Ultimately, Barbie herself rejects her plastic fantasy life, and decides she would rather become a woman in the flesh, with all that entails, including health issues, growing old, and dying. As powerful of an idea as Barbie is, she would rather be real.

I thought that the movie was, in fact, brilliant when it made its existential points. I mean, I know I’m reading a lot into it, but isn’t coming into imperfect physical form out of the realm of archetypes exactly what it means to be human?

Where the movie was a hot mess was in its plot execution. The Mattel executives with their antics seemed superfluous, and the whole patriarchy wars plot was silly. But I suppose that was the point – this film is self-consciously ridiculous, being a satire of our society as seen through the lens of imaginary play with a line of dolls representing fashionable, feminine, and highly successful career women. I suppose I might come to appreciate the plot more on a rewatch, and just the fact that I would like to rewatch the film says a lot about its quality.

Going back to Ken and his obsession with patriarchy, it’s interesting that at the top of the movie, Ken is the only character with a motivation, an important one from a plot perspective. Barbieland is not a dream world for him, as he is perpetually frustrated in his quest for Barbie’s attention. His obsession with Barbie and with winning her over reminded me of a point that Camille Paglia makes in Sexual Personae, which is that women have power over men because women keep men in a perpetual state of anxiety as they seek women’s approval. This goes all the way back to their mothers and the Oedipal complex.

That’s why men made a patriarchy! To carve out an exclusive masculine sphere of competition and achievement where men can work hard to impress women. According to the Futurama educational video I Dated a Robot, all of civilization is just an effort to impress the opposite sex. At least, that’s the benign interpretation of patriarchy. In the less friendly version of patriarchy, men dominate women with force in order to avoid the pain of rejection, and to control women’s lifegiving power. As Handmaid’s Tale author Margaret Atwood puts it, “Men are afraid that women will laugh at them. Women are afraid that men will kill them.”

Luckily for Barbie, plastic dolls can’t be hurt or killed, and Ken’s patriarchal temper tantrum becomes a comic spectacle that transforms into a thrilling song and dance number. But this is in an imaginary world, of course. In reality, men must develop confidence and independence to become the partners that women need. Which Ken does, in his way, though Barbie leaves him behind in the end.

l can understand why the message of this movie would gall right wingers and reactionary “feminist backlash” young men. Thanks to the successes of feminism, as symbolized by the very existence of Barbie, Millennial women are poised to be the most financially independent generation of women in history. Meanwhile, Millennial men have been falling behind, and young adults are delaying marriage and family formation. This could arguably be interpreted as a sign that feminism has, in fact, run roughshod over the traditional family, which is the gist of the complaint against Barbie as “woke feminism destroying us all.”

So what could have just been a fun summer blockbuster and product promotion movie has turned into a flashpoint in the Culture Wars. I guess that’s what Warner Bros. gets for hiring an intelligent director. Personally, I don’t think the problems facing young people today should or could be fixed by “restoring patriarchy.” I think most people agree with that sentiment, which is why the movie is a smashing success at the box office, and the haters are on the fringes.

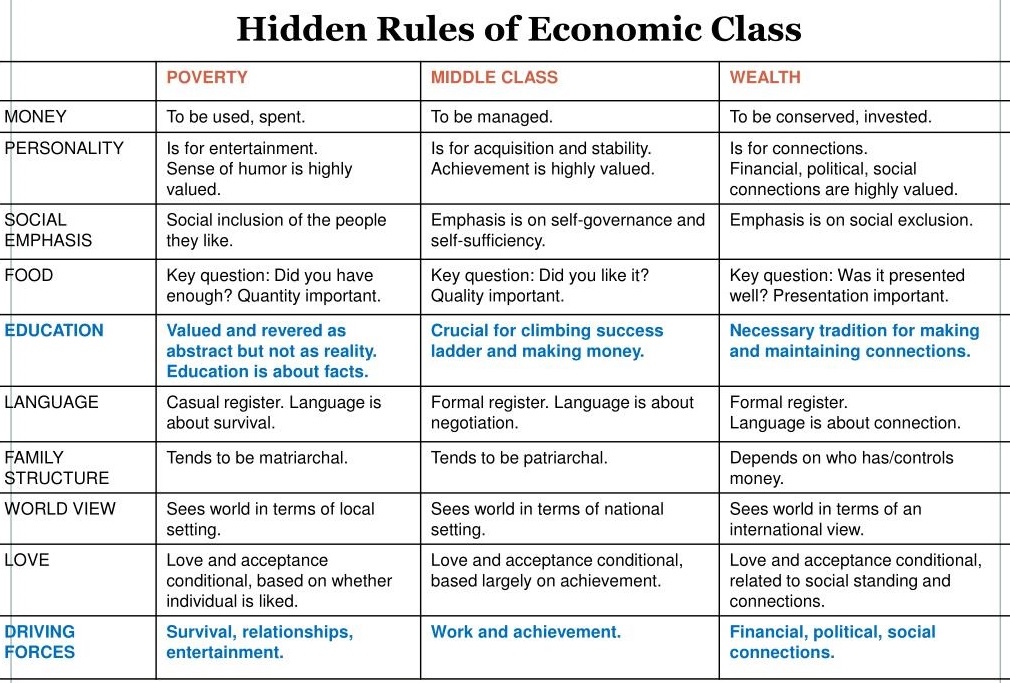

The primary reason the young generation isn’t forming families has nothing to do with the culture; it’s because of financial insecurity. Fixing that issue requires reforms to our economic system, with new laws and tax structures. Barbie doesn’t address any of this; instead, it promises that you can find fulfillment in life, provided you are grounded in youself. In a way, it is an apology for the current system, which focuses on the individual as a self-reliant unit, thriving in a consumer economy. This is an understandable worldview for Mattel to promote. After all, they have dolls to sell. But if Barbie is undermining society in any way, it’s not by being woke, but rather by supporting the neoliberal economic regime, which for decades has been eroding away the middle class.

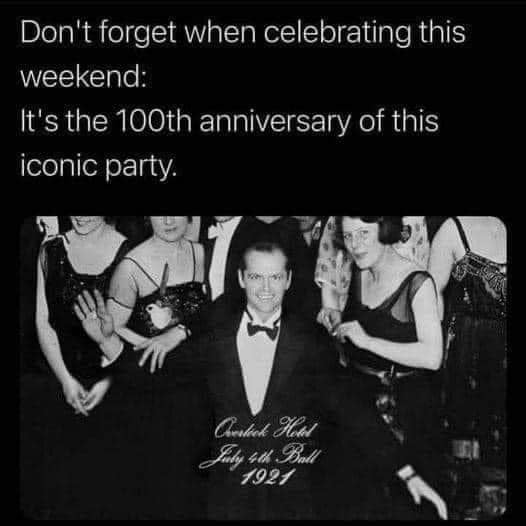

Well there, I’ve probably put way too much thought into Barbie. But hey, if a movie makes you think, then it’s done its job. Aside from its message, the film also has wit, charm, and tremendous visual appeal. I expect it will be awarded for its impressive art design. There are tons of recreations of toys and outfits from the Barbieverse (is that a thing?), plus fun original songs by top pop artists, and sly references to other films.

That’s it from me, soon we are off to beach. Maybe we’ll see Barbie again while we’re there. Stay cool, folks, and remember – you are Kenough.