The Walking Dead Finale and How This Show Captured the Zeitgeist

Tonight the series finale of The Walking Dead will be broadcast on AMC. I have been a fan of this show since it began way back in 2010, which seems like a lifetime ago. When it premiered, I was living in North Carolina, and watched it with my roommate at the time. I found it to be a compelling, immersive horror story. It gave me the creeps and made me want to lock up the house and peek out the windows to check for zombies. But I still looked forward to new episodes every Sunday; as Bob Calvert sings, we like to be frightened.

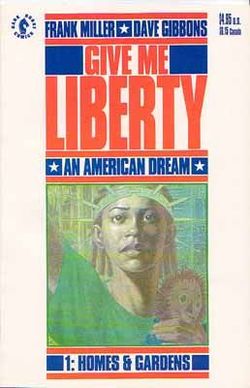

Over the years, my roommate moved out, and so I watched the show alone. Then I became a cord-cutter (that is, I cancelled my cable subscription), so I had to wait for seasons to come to Netflix before I could catch up on episodes. I also started reading the comics, and I loved to compare and contrast the comics with the TV series. For example, of the four characters depicted in the series finale promo shot above, one is never in the comic, and one dies early on. Of the other two, one wanders off and is never heard from again, and only the last one actually remains relevant to the story all the way to the end.

It’s understandable that the writers of the TV show would want to deviate from the comic series storyline, to keep fans guessing. The writers also didn’t have much choice, for two basic reasons. One is that the actors playing the children aged faster than the story timeline; there’s no way their characters could have a story arc to match the one in the comics, over a 5 or 10 year period IRL. The other reason is that sometimes the stars just wanted to leave the show.

The main character, Rick Grimes, had to be written out of the TV show because the actor playing him wanted to spend more time with his family. In my opinion, this was a grave blow to the series, since the comic’s basic story is how Rick Grimes manages to build a community out of a ravaged post-apocalyptic society. The comic series has a kind of triumphal ending, after dragging the reader through all sorts of harrowing hell. Can the TV series accomplish something similar? I guess we’ll find out soon enough. But I think the TV show kind of got lost at times, because all it could do was recycle plot lines with new sets of characters, as actors came and went. It just didn’t achieve a strong overarching story arc, as the comic does.

Another interesting difference between the comic and the TV show is that the comic is actually much more violent, and also has foul language and sexual content that is absent from the TV version. This, of course, is because the TV show is on basic cable; AMC content is not TV-MA rated, as far as I know. As I recall, the TV show is as edgy as it is at all only because it comes on late at night. The comic also, as a rule, has more interesting zombies, since it’s easier to draw animated corpses in various states of decay, than it is to construct them with prosthetics or paint them with CGI. The TV show has hordes of fully clothed, barely decayed zombies – that is, extras wearing face makeup – whereas the zombie hordes in the comic have bones poking out and guts hanging out every which way.

The difference in the intensity of the violence on the TV show became very significant about halfway through the show’s run. This was around the peak of the show’s popularity, at the end of season 6 and beginning of season 7. At this point, I was watching new episodes at a movie theater in North Carolina. Yep, this theater showed them as they premiered, and free of charge. The theater was next to a college campus, and would be packed full of young people. I would usually go by myself (though I did convince a friend to join me a few times), and would have a couple of beers while I watched. It was a lot of fun.

Season 6 ended with a cliff hanger, and there was all this buzz and excitement when season 7 started. But in the first episode of season 7, a beloved character was brutally murdered. I still remember the shockwave through the audience when it happened. The next Sunday, the crowd was maybe half the size. That moment practically killed the show; it’s popularity plummeted after that. But the irony is that in this instance, the TV show was being completely faithful to the comic book. The same exact murder happens in the comic, and because of that I wasn’t surprised by it at all. And as for the brutality of it, well, the comic had always been that violent; it was like the TV show was catching up. But this was too much, I think, for most fans, and the TV series never recovered it’s viewership levels after that.

When I moved to Pennsylvania, I finished reading the comic books, and continued watching the TV show with Aileen. At this point, in order to stay current, we purchased the seasons on Amazon prime (yeesh), and then eventually got an AMC+ subscription. Tonight, we’ll be able to watch the last episode, on our streaming smart TV. I’m very curious to see how its ending compares to the one in the comic series.

While I do think the comic books are better, because they have a more coherent story and actually have a point, I have enjoyed the show, and its creators and producers deserve kudos for their achievement. 12 years (11 if you consider the pandemic break) is an amazing run for a television series. It’s been quite a journey for the characters who survived this long, and for the audience that has stuck with the show to the end.

Aileen and I have discussed why this show is popular. She says it’s because it reminds people that no matter how bad their lives get, it’s nothing like what the characters in The Walking Dead have to go through. And she agrees with me that the series captures the mood of the Fourth Turning. As I’ve blogged before, it’s like the reckoning that Gen X has been waiting their whole lives for, finally coming to pass. It parallels the state of our world today, with everything falling apart, and group pitted against group. I just hope that in the show, and in real life, the good guys win.